Absent the efforts of the thousands of nonprofits in Illinois, the cultural and social fabric of the state likely would be worn threadbare.

Illinois nonprofits work in almost invisible ways, filling roles that many may not realize. The government relies on nonprofits to provide human services to Illinois residents who need food, counseling, shelter and health care. Nonprofits keep culture alive in communities across the state through theater companies, symphonies and arts education programs. The state’s nonprofit network includes multibillion-dollar institutions of higher learning such as the University of Chicago, as well as world premiere science museums and hospitals. Nonprofit institutions fill certain niches — in traditional and nontraditional ways — such as the Raggedy Ann and Andy Museum in Arcola or the Leather Archives and Museum in Chicago, dedicated to preserving the history of fetishism. The organizations also advocate for causes that ordinary citizens don’t have the time for — to be a watchdog of government or of society itself.

An ordinary street scene in any given Illinois town can illustrate the reach that thousands of nonprofit workers and organizations have each year. Flyers on a building may advertise an upcoming production of a nonprofit theater group. The air may be a bit more breathable because of the efforts of nonprofit environmental groups. A homeless family may be in a shelter instead of on the street because of the dedication of a nonprofit.

“Oftentimes, people really associate the word ‘charity’ or ‘nonprofit’ with those that help the less fortunate — the homeless shelters, food banks. They’re less apt to think about a cultural institution like a theater being a nonprofit,” says Sandra Miniutti, spokeswoman for Charity Navigator, a New Jersey-based organization that evaluates charities. “The diversity is a positive thing.”

Within Illinois’ nonprofit network, more than 427,000 workers toil away for their individual causes. Here’s a look at some of the diverse roles Illinois nonprofits play in the state:

Southern Illinois Community Foundation

In Marion, Patricia Bauer racks up the miles on her Honda Accord trying to build a name for the Southern Illinois Community Foundation in the 17 counties that it serves.

“We’re young and we’re rural, and it takes a long time to educate people to get them to the point they’re ready to use the foundation,” says Bauer, the foundation’s executive director.

At 10 years old, the foundation is trying to stand on its own feet after being nursed along from infancy through a program run by the Grand Victoria Foundation, an Elgin-based organization that has spent the past several years trying to create a stronger infrastructure for philanthropy throughout the state. When the effort started in 2001, community foundations were a fledgling sector of the nonprofit world in Illinois, says Nancy Fishman, executive director of the foundation.

“Philanthropy and civic leadership are concentrated in certain parts of the state and not others. We set out to stimulate philanthropy, to create a more robust landscape for it,” Fishman says.

The Grand Victoria Foundation, which was established in 1996 by the Grand Victoria Casino, has provided operating support to community foundations throughout Illinois and recently pledged $42 million more to help those organizations continue with their action plans over the next three years.

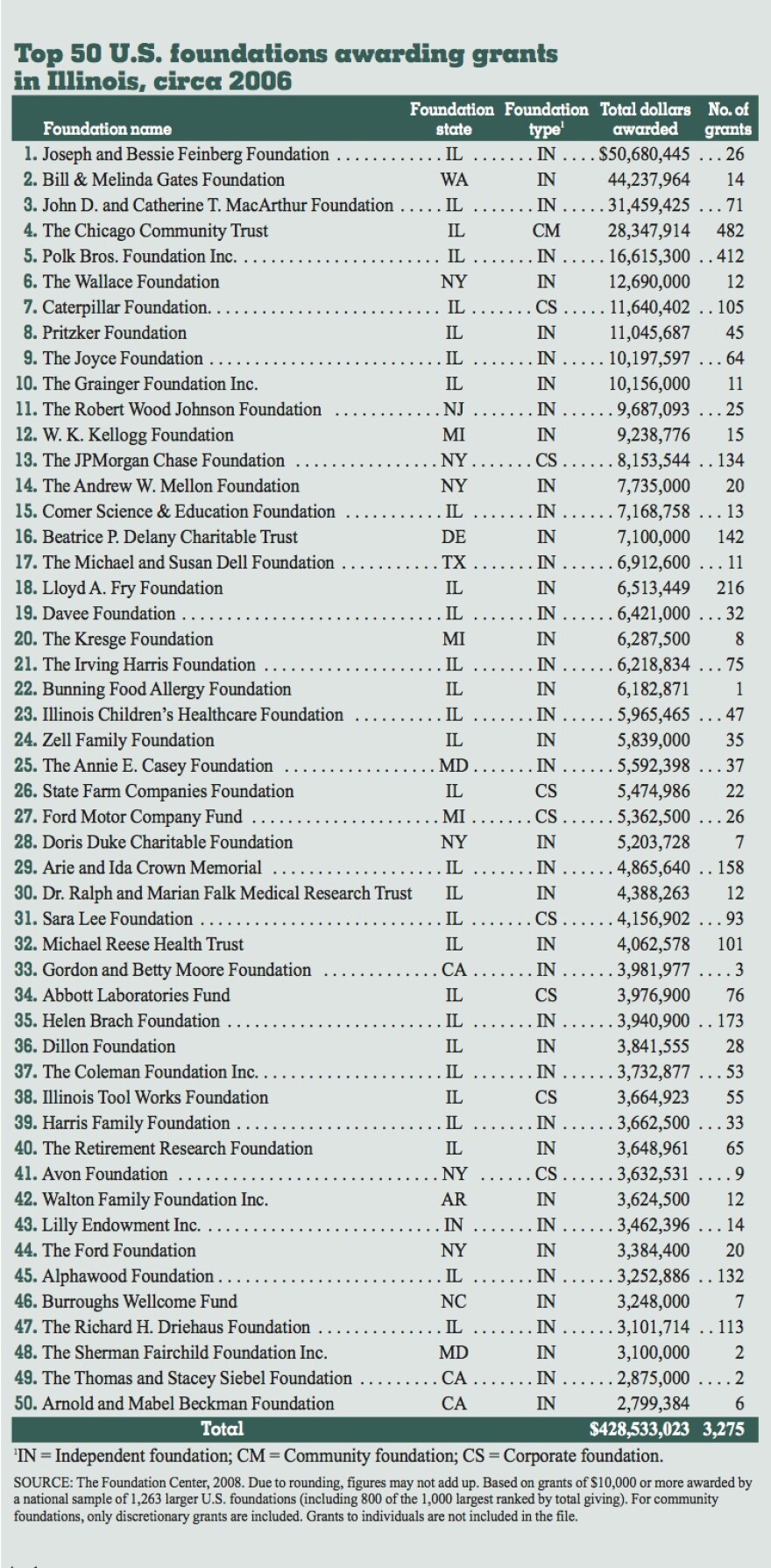

For nonprofits in rural parts of the state, there are only so many doors to knock on to ask for money — unlike Chicago where many large, well-established foundations exist, Bauer says.

“They keep their money in Chicago,” she says. “There is great need in Chicago, but I think they just don’t know how poor southern Illinois is. … It’s always been a struggle, and we’ve always gotten our funding from the people who live here.”

Community foundations act as a bank for the charitable dollars of its residents, then funnel the money to local nonprofits. They can also serve as gatekeepers, vetting the efficiency of nonprofit organizations that may receive the money.

Last year, the Southern Illinois Community Foundation handed out about $401,000 in grants to local nonprofits.

Emil Spees, 73, of Carbondale, and his wife, Edith, made a gift to the Southern Illinois Community Foundation last year to establish endowment funds that benefit charities of their choice. “We felt assured the money would be well taken care of and well invested,” he says.

Providence Family Services

“Sister Patty” walks briskly through the old brick convent where she has lived and worked for the past 32 years in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood.

While working as a teacher and principal in the Maternity BVM Catholic Elementary School next door, Sister Patricia Fillenwarth noticed that many families in the neighborhood could benefit from counseling, especially in their native Spanish. But none could afford to pay for such a service. So in 1991, she enrolled in school herself, became a bilingual counselor and opened Providence Family Services, persuading the priest to give her space in the convent to use for her small program.

Slowly, Sister Patty and her band of volunteers have taken over much of the building as they continue to add new services to help their neighbors. As she leads a tour through the facility, kids and volunteers from local colleges sit at tables throughout the convent, going over workbooks and flashcards for the after-school tutoring program run by the retired sister. When classes in English as a second language were needed, Sister Patty went to Wright College about partnering to provide the classes to parents. A former preschool room in the basement is now used as a babysitting room where kids play while their parents learn English. An old laundry room was painted lavender and is filled with donated computers for a computer class.

Sister Patty sees about 30 clients a week in a small, dimly lit corner office. A part-time counselor also has her own list of clients. Most pay about $8 for a counseling session; some can’t pay at all. “They’re three months behind on rent, gas is about to be shut off. I’m not going to add to their stress. Somehow they keep going,” she says.

This year the agency has a development person for the first time working to build its yearly $120,000 budget.

“She writes and writes and writes, but nobody’s got any money to give you,” Sister Patty says.

The agency mostly gets by on donations, small grants and the $3,500 from an annual rummage sale in the church basement.

Sister Patty is worried about other needs she sees. “I get more requests now for food and clothing, and we don’t do that because we don’t have space or a social worker,” she says. “There are fewer and fewer places to refer people to.

“I don’t know what people do, to tell you the truth,” she says. “I’m sorry we can’t do that, too.”

Prairie Rivers Network

If a company wants to increase the amount of pollution it dumps into Illinois waterways, it should expect the eye of the Prairie Rivers Network upon it.

“We’re in a watchdog role — watching them, commenting, getting involved in negotiations to say, ‘Can’t you do better than this proposal we’re seeing?’” says Glynnis Collins, executive director of the Champaign-based nonprofit.

Each week, Traci Barkley, a water resources scientist, combs through permits on file with the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency and other agencies to make sure industrial facilities and sewage treatment plants are minding the Clean Water Act. It’s work that average citizens often don’t have the time or expertise to do.

“There’s always pressure from the polluting industries,” Barkley says. “We have to maintain pressure on the other side, as well.”

Among its recent accomplishments, the network joined a coalition to get power plants in Illinois to reduce mercury emissions. The network also recently scored a victory in making sure clean waters are kept clean by not allowing polluters to dump higher levels of toxins into the water because the waterway started at a cleaner level.

Marcia Willhite, chief of the bureau of water for the Illinois EPA, says the agency has a good working relationship with the network and its staff of scientists. The two parties don’t always agree. “But generally, I think they do a good job of filling that environmental advocacy role,” Willhite says.

Belleville Philharmonic Orchestra

In 1866, a group of German immigrants returning from the Civil War had a meeting in Belleville to discuss bringing their love of music to life in the United States. They rehearsed for a month and had their first concert on January 26, 1867.

“It’s been going ever since,” says Robert Charles Howard, conductor of the Belleville Philharmonic Orchestra. He has a pile of programs stretching back to those early days that proves as much.

“Belleville has always been a music town,” says Erna Meyer, 83, who has played violin in the orchestra for 53 years. “It is the second-oldest continuously playing orchestra in the whole United States. It’s quite an honor to be part of that.”

The nonprofit runs on a budget of about $80,000, cobbled together from program ads, concert sponsorships, gifts from the community, ticket sales and a grant from the Illinois Arts Council. The musicians are mostly volunteers with other professions who come together every Thursday night to practice in the red brick building the orchestra has owned for more than a century. There are lawyers, professors, ministers, high school students and senior citizens.

“On Thursday night, people come from wherever they are, and they’re all doing it for fulfillment and enrichment,” Howard says. “We need the life of all these different community connections coming out in the music. … We’re part of what Belleville’s always been.”

Community Support Services

The seven concrete stairs to Patricia Tejeda’s home in suburban Chicago are steep, especially when the petite woman is alone and has to carry her 9-year-old daughter Ana and Ana’s wheelchair up the steps while also transporting her 5-month-old baby and 5-year-old son.

On many days, she does it, but Community Support Services Inc. in the Chicago suburb of Brookfield provides a break for her.

Her case manager, Samantha Cortez, is comfortable enough in the Tejeda home to pick up the baby and make him laugh, while also helping the 30-year-old Spanish-speaking mother to schedule doctor appointments, school meetings and respite care workers to come into the home to care for Ana. Ana suffers from cerebral palsy and a seizure disorder and cannot walk or talk, save for a few words.

Community Support Services, which operates on a budget of about $6 million, serves 650 children, adults and seniors. After the start of the fiscal year, the state cut the agency’s grant for respite care and family support by $88,000 or 12 percent, says president Gaye Preston. That meant every family, including Ana’s, had their respite care slashed by about 20 percent.

Other funding sources could not help the organization make up the difference. The agency’s annual golf outing brought in just about half of the $100,000 it usually counts on, Preston says. The agency also downsized plans to partner with other nonprofits to open a new building in suburban Cicero as part of an effort to reach the underserved population in the area.

“We didn’t want to stop serving people, but we had to respond in some way,” Preston says of the changes.

With the loss of hours, Tejeda faces those stairs alone more days. She is grateful for the help but could always use more assistance. In Spanish, Tejeda says,“It helps us a lot. Ana enjoys it, and we get to rest.”

Philanthropist recalls her humble start

Maria Bechily’s first philanthropic assignment was to teach a catechism class in her native Cuba at the age of 12. That same year, she was one of thousands of children airlifted out of Cuba and placed in U.S. foster homes.

She landed in Chicago, and social workers from Catholic Charities placed her in a foster home, where she lived until her parents were able to join her in the United States about a year and a half later.

“I was touched very deeply by my social workers,” says Bechily. “They reinforced in me the importance of social agencies.”

After college, Bechily became a social worker for the very agency that had helped her as a child, Catholic Charities. There, she even ran into her former social workers.

Decades later, she has built a resume devoted to philanthropic pursuits, from supporting arts education at the Goodman Theatre to co-chairing a campaign to raise millions to build the new Prentice Women’s Hospital at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. She is also a member of the executive committee of the Chicago Community Trust.

Her career path took her to a job in the office of U.S. Sen. Alan Dixon, then to a Spanish language television station before she started her own public relations firm specializing in the growing Latino market.

Now semi-retired, Bechily says she is lucky to be able to devote time to the nonprofit boards she serves on. While raising money for the various causes she supports, Bechily says she’s learned the importance of doing her homework and that “you can never spend someone else’s money for them.”

“One has to really know who it is you are approaching,” she says.

She also says that people may hold onto the misperception that you have to have a lot of money to be involved in philanthropic efforts.

“It’s not just about writing a check,” she says. “Thought leadership is very important.”

For the Northwestern fundraising campaign, the team that Bechily co-chaired surpassed the $150 million goal set for them, raising $207 million.

“When raising money for a hospital like Northwestern Memorial Hospital, it’s a very different experience, as potential donors have a very close and oftentimes emotional connection to a hospital,” she says.

Those who work with Bechily in various philanthropic projects describe her as a conscientious board member who doesn’t take her work lightly. “To understand Maria, you have to understand that she approaches everything with passion and vision,” says Stephen Falk, president of the Northwestern Memorial Foundation. “She’s very empathetic toward the community and will often challenge me and others by asking, ‘Are you doing enough for the community?’” he says.

Her current pet project is Nuestro Futuro, an effort at the Chicago Community Trust to help build Latino philanthropic efforts. As a member of the executive committee of the foundation, Bechily says she sees “all kinds of heroes out there doing amazing things.”

Giving as a family affair

Rob Tracy is a “3g.” In Tracy family lingo, that means third generation.

At 27, he sits on the board of the Tracy Family Foundation with the “2gs,” or second generation board members. Created in 1997 with profits from a successful business founded by Robert and Dorothy Tracy, the nonprofit foundation now run by the Tracy offspring aims to improve the lives of people in the Mount Sterling area in west-central Illinois.

Rob Tracy, who is earning a master’s degree in business administration at the University of Denver, travels back to Illinois for annual board meetings and has conference calls with his uncles, aunts and cousins about once a month to discuss foundation business.

On the board, no one pulls rank, and the involvement of “3gs” is encouraged. “Everyone’s opinions are valued,” says Rob Tracy.

Robert and Dorothy Tracy had 12 children, raising their brood in Mount Sterling, where Robert Tracy started Dot Foods, a food redistribution company, in 1960. Today, the company is a major employer in the area, and those 12 children have 12 spouses, including Republican state Rep. Jil Tracy, and 47 kids.

In its first year, the Tracy Family Foundation gave $38,000 to charities. Last year, it gave just under $2 million in grants, says Jean Buckley, president of the board. This year the foundation will give away about $1.6 million, she says.

The foundation focuses on causes that benefit children, families and youth and is currently intent on improving area schools. The foundation has funded a consultant to help local public and private schools concentrate on the best teaching practices. Five years ago, the foundation and the company donated funds to build a YMCA in Mount Sterling.

Philip Krupps, executive vice president of Brown County State Bank in Mount Sterling, says the foundation also helped spur a movement in Brown County for a complete communitywide assessment.

“They were very proactive on addressing the issue, not just in a monetary sense, but really empowering people to see what lies ahead and how to handle it,” says Krupps, who is also president of the local United Way.

The Tracy family has an annual meeting at a hotel or a resort where members are updated on the business and the foundation. Pat Tracy, chairman of Dot foods and a foundation trustee, jokes that the family doesn’t torture anyone by making one person host the huge group of Tracys at his or her home. The board meetings are businesslike but filled with family banter.

“We’re kind of a process-oriented tribe. We follow processes like in the business,” says Pat Tracy. “We’ve always had a pretty informal air to our work together.”

Crystal Yednak is a Chicago-based free-lance writer.

Definitions

Nonprofit organizations that operate to advance religious, charitable, scientific, literary or educational purposes are eligible for tax exempt status under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.

The organizations cannot be run to benefit private interests or one particular individual. All 501(c)(3) organizations are banned from participating or intervening in a political campaign on behalf of any candidate for elective public office, according to the code.

The IRS classifies charitable organizations as either a public charity or a private foundation.

Public charities include churches, hospitals, medical research organizations, schools, colleges and universities. The organizations have an active fundraising program and receive money from multiple sources that may include the general public, the government, corporations and private foundations. They may receive income from activities that further the organization’s charitable goals.

A private foundation has just one major source of funding, usually from one family or one corporation. The primary focus of most private foundations is to hand out grants to other charitable organizations.

SOURCE: Internal Revenue Service

This is the second installment of a three-part series on the status of nonprofit organizations in Illinois. The articles were made possible by a grant from the Donors Forum, a Chicago-based umbrella association for foundations and other charitable organizations. The Donors Forum agreed to exert no editorial control over the content of the articles or the selection of the writers and photographers and did not review the reports before publication. All decisions on those matters were made by the editorial staff of Illinois Issues. The final installment of the series will appear in the fall. — Dana Heupel, executive editor

Illinois Issues, June 2009