The political spotlight has shifted to the election, but the state budget crisis continues to cost the people of Illinois.

Editor’s note: This story marks the launch of the Past Due initiative at NPR Illinois. Past Due is a commitment by NPR Illinois to cover the state's historic budget impasse and what it means to you. Click here to share your personal story of how the budget impasse has affected your life.

The Illinois State Fair is an unofficial start of sorts to state level campaign season in Illinois. Although — with all the money being dumped into legislative races this year, much of it coming from Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner — political ads and mailers were already flying by the time the fair kicked off in August.

At fair events, Rauner and Democratic House Speaker Michael Madigan rallied the troops, mostly against each other, and made the cases for those in attendance should support their candidates. Rauner didn’t mention Madigan by name in his speech during the Governor’s Day festivities at the fair. But buttons, featuring a picture of a young, smiling Madigan, were distributed to advocate for one of the governor’s signature issues, term limits.

“A corrupt political machine has taken over our home. And they are strangling our state. They are driving jobs away. They are raising your taxes,” Rauner told the crowd. “It’s a machine that doesn’t care about the people of Illinois. It’s a machine that cares only about power. Well, you know what we’re going to do ladies and gentleman, we’re are going to beat that machine and restore power to the people of Illinois.”

In his speech at a breakfast kicking off Democrat Day, Madigan said two things should unite Democrats in the state. “No. 1, I think we can come together in opposition to the extremism of Donald Trump. No. 2, I think we can all come together in opposition to the extremism of Bruce Rauner.”

There were nifty souvenirs and plenty of red meat, but what neither of them offered in their political speeches were proposed solutions to the state’s budget crisis. The impasse between the two men and members of their respective parties in the legislature has left the state and its citizens paying the price in some very real ways.

Before kicking off the campaign season, the General Assembly approved and Rauner signed into law spending meant to allow areas of state government that had not been fully funded — or in some cases funded at all — for the last year to limp along for another six months, until after the November election.

The legislation has come to be known as the “stopgap budget.”

Laurence Msall, who is president of the fiscal watchdog group the Civic Federation, bristles at that characterization. “The stopgap is not a budget. It defies the definition of what a budget is,” he says.

Msall says having a budget would mean that the state’s leaders had reasonably estimated what the state would spend in this fiscal year, what financial obligations it would incur under the law for things like the state’s pension payment and debt service and how much revenue it would bring in. Then, lawmakers and the governor would work out a plan to either cut costs, increase taxes or do both to make the total of the first two — spending and nondiscretionary costs — match up with the last: revenues. A budget would also cover a designated period of time, also known as a fiscal year.

It’s Public Finance 101, really, but it’s also something lawmakers and the governor have failed to do since Rauner was sworn into office last year.

Spending authority in the stopgap legislation only lasts until the end of December. So far, other than vague statements about hoping to come together after the election and hash out a deal, there’s been no indication from the governor or legislators of what will happen when the so-called stopgap budget runs out or how organizations that rely on state funding should plan for it. Will they get more money in January? Should they start cutting now? Will service providers who contracted with the state get paid for the work they are currently doing? What about the things, like employee health insurance, that aren’t paid for in the stopgap? These are all currently open questions.

Cost to taxpayers

When Illinois started last fiscal year without a budget, courts stepped in and forced the state to continue funding Medicaid coverage, employee pay and costs associated with legal agreements called consent decrees. The state also does some automatic spending each year under law, including making payments on its debt and into the pension systems for public employees. Rauner signed funding for K-12 education. Schools opened on time and the biggest pressure to get a full budget worked out was lifted.

Illinois didn’t fully fund higher education or pay for utilities, like gas and water for public buildings, or basic operating needs, like office supplies for state agencies and food for prisoners. It also didn’t pay for social services not covered by Medicaid. But it still managed to rack up a nearly $4 billion deficit last fiscal year. The Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability (COGFA), a bipartisan legislative panel, estimates that deficit will grow to $7.8 billion by the end of the current fiscal year. The Governor’s Office of Management and Budget disagrees. Its projection pegs the Fiscal Year 2017 deficit at $5.4 billion.

In other words, just because the state doesn’t have a full budget, that doesn’t mean the money isn’t going out the door. The state is spending more than it takes in, by a long shot.

How is Illinois coping with the fact that it’s on the hook to spend much more than it has? Mostly by just not paying its bills. The comptroller’s office estimates that the bill backlog is $8.4 billion. The backlog is projected to hit $14 billion by the end of the current fiscal year, which started on July 1 and lasts until the end of June next year.

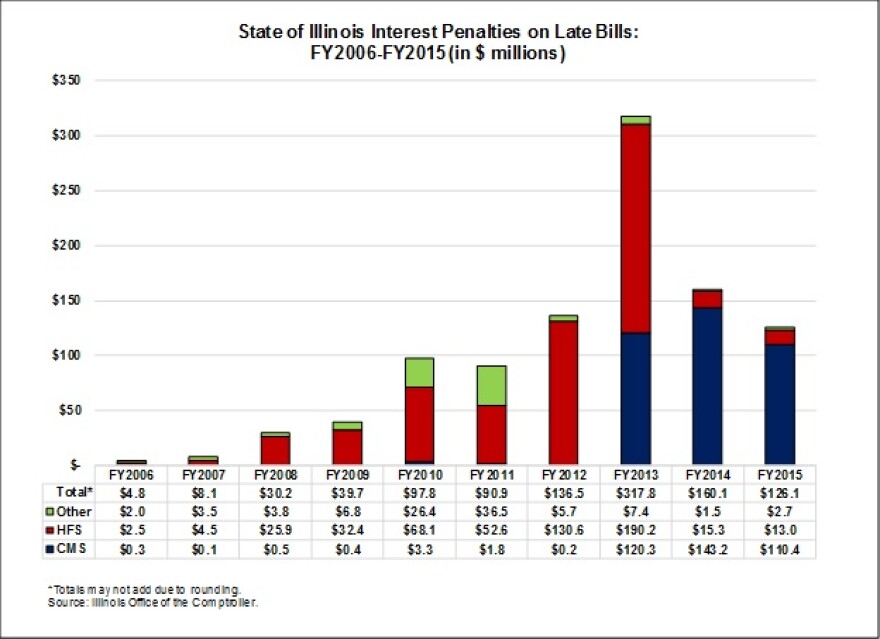

Putting off those payments comes at a price. Under state law, Illinois pays interest on bills it lets sit for months unpaid. A February report from the Civic Federation found that the state paid about $1 billion in interest charges over the last decade. And the lack of real a budget means those penalties will continue to rack up.

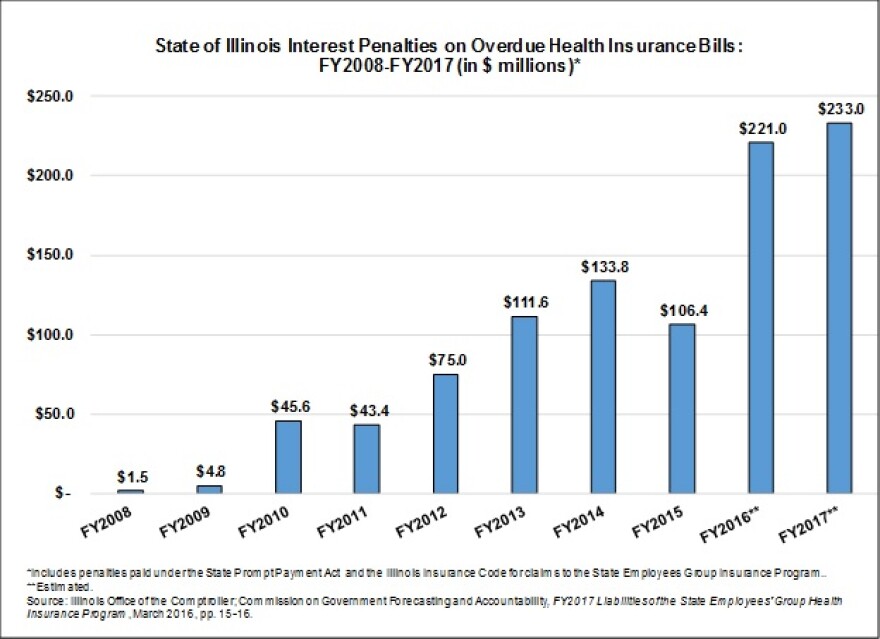

A March report from COGFA estimated that the state will pay more than $400 million in combined interest payment for the current fiscal year and last fiscal year on overdue bills from health care providers who treated public employees. The report said that interest penalties are expected to cost the state more than both dental and life insurance coverage for employees.

Illinois has made a habit in recent years of not fully funding health care coverage for employees, and the impasse certainly did not put an end to that. Payments to the public employee group health insurance plan were not made the year the state went without a budget, and no funding for it was included in the stopgap.

Illinois is also paying more when it borrows because of its fiscal irresponsibility. Martin Luby, an associate professor in the School of Public Service at DePaul University, has been tracking these costs when Illinois sells bonds. He looks at what the interest costs could have been if the state had a better credit rating. It currently has the lowest of any state in the county. “[The state’s credit ratings have] declined further over the last year in light of the fact that we don’t have a budget. So just like a person’s credit, and individual’s or a household’s credit, as the credit rating goes down the cost of borrowing goes up because the likelihood of default … goes up.”

When the state borrowed in June to pay for construction projects, Luby says it paid a projected $70 million more because of its low credit rating.

Much like the bill backlog, the state’s low credit rating is nothing new. Luby notes that it has been slipping for about a decade. But, he says that the downgrades in the six months before the sale cost the state at least $12 million of that $70 million. Luby is also a visiting senior fellow at the University of Illinois Institute of Government and Public Affairs, which published his analysis.

The state’s poor fiscal standing is dragging down the credit ratings of other entities that rely on it for money, including most of Illinois’ public universities. Luby says they too pay more for borrowing. “In the capital markets, we call that the ‘Illinois penalty.’”

A recent report from the Chicago-based nonprofit Truth in Accounting found that the state’s total debt burden, when divided across all of its taxpayers, comes to $45,500 per person.

That total includes costs that Illinois will not be paying right away, such as the unfunded pension liability. But Sheila Weinberg, the group’s founder and chief executive officer, points out that taxpayers will be paying that debt off, whether it’s sooner or later.

“The employees have already earned these benefits. That state has already incurred these costs,” she says. “Do you owe your credit card balance if you’re planning to pay it off over time? Yeah. You still owe that balance, and you still owe it today even though you plan to pay it off over time.”

That analysis doesn’t cover the time the state has gone without a budget, but Weinberg says it will only have made matter worse.

Given the state’s level of debt, Illinois’ fiscal house was clearly already aflame before the impasse. But when it comes to what elected officials will ultimately have to ask of taxpayers, not having a budget for a year and a half will be like throwing gas on that fire.

“We are spending so much more money than we have available that we’re going to make the solution that much harder. We’re digging the hole that much deeper,” Msall says.

He says that taxpayers will end up forking over more and getting less in terms of services for it. And the longer there’s no solution, the bigger the tax increases and cuts will need to be to fix it.

“Unless we’re going to get rid of higher education in large parts at the state, close major universities or stop providing health insurance to new (public) employees, there’s not going to be enough cutting that can be done to balance the state’s budget,” he says.

Human cost

Before the stopgap budget, social service providers were only being paid for services that are part of the Medicaid program, which pools state and federal money to provide health care for the poor, or a legal agreement the state made in the past.

The list of services that don’t fall into that category is long and varied. It includes, mental health and addiction treatment, services for victims of sexual assault and domestic violence, support for the homeless and Meals on Wheels programs that bring food to seniors. For most of these programs, providers had contracts with the state last fiscal year, despite there being no budget to pay them.

The stopgap plan included funding for some of these programs. But it is unclear who will get paid, how much and for how long. The money would typically cover a 12-month period, but it seems to be intended to instead cover 18 months.

Dan Lesser, director of economic justice at the Chicago-based Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, says most, if not all, of the money will be needed to cover the cost of services already administered under contract for last fiscal year. “There’s not going to be anything left to pay for fiscal year ’17 for services that are currently being provided.”

Lesser says providers may soon find themselves back in the same place they were last year, having to cut programs, make layoffs and try to take out loans. “All the bad things that happened over the course of fiscal year ’16 are either happening or about to happen,” he says.

David Lloyd, director of Voice for Illinois Children’s Fiscal Policy Center, agrees. “That will only get worse as the year goes along and the funding that was just passed goes further and further back in the review mirror,” he says. “It could be really devastating if we don‘t pass a full year’s budget that’s funded with adequate revenue.”

Both Lloyd and Lesser say that providers will be hesitant to bring back staff who have been laid off and restore programs that were cut because they don’t know what to expect from the state. “The question remains: will they get paid?” Lesser says.

Both also say the situation will cause long-term damage because it’s hurting the future prospects of today’s children. “The costs are really staggering. When we’re not putting these basic investments in children and their families, we set ourselves up and them up for failure for years to come,” Lloyd, says.

Lesser asks: “What kind of state do we want to live in? Do we want to live in a state where one in every five children is growing up in poverty and having their chances in life sabotaged by that — something they have no control over?”

Msall says he hopes people who think the issue doesn’t touch their lives will begin to recognize the toll it’s taking on some of their neighbors. “For people who don’t think the state budget affects them, I would challenge them to look around in their community and see the people that are on the streets looking for help,” he says. “When you engage with them, you quickly realize that these people need more services than whatever they can collect in that cup are going to provide. That’s the impact of the state budget crisis.”

Economic cost

Like the human costs, the economic costs of the lack of a budget can be difficult to quantify. There are obvious ways the state’s economy is affected, such as the toll layoffs and dropping enrollment rates take on university towns. Eastern Illinois University in Charleston has been among the hardest hit. The school laid off nearly 400 employees after not receiving its usual funding from the state, and undergraduate enrollment is down by more than 17 percent.

Chicago State University, the school that came the closest to shutting its doors during the more than nine months Illinois wasn’t funding higher educating at all, saw a 32 percent drop in undergraduate enrollment this fall. Only 86 freshmen signed up for classes at CSU this year.

“What’s happening in higher education is really harmful to the state. We’ve been essentially dismantling, piece by piece, our higher education system,” says Lloyd. “That will have a very negative long-term effect on our state’s economy.” He says that educational attainment for parents is linked to better outcomes for children.

The layoffs that human service providers have made have an economic impact, too. “When they layoff staff, that’s less money that’s flowing through our local communities and local economies,” Lloyd says. Those who go without services may also be unable to work without the support.

Staggering deficits put much of the attention on the money the state is spending, but the money it’s not spending is a problem, too. As it grapples with red ink, Illinois isn’t investing in its infrastructure.

Luby calls overdue maintenance of roads, bridges and other infrastructure the state’s third deficit. The other two are the operating budget shortfall and the unfunded pension liability. He pegs the so-called third deficit as anywhere between $20 billion and $30 billion, depending on how the spending was carried out and what sort of borrowing deals the state might get.

“Infrastructure has to be at the table. It needs to be considered. And that’s one thing that has probably not been the case because it’s easy to ignore when you have these more kind of near term financial crises that you have to deal with,” Luby says.

He says that beyond annoyances like potholes and congestion, the lack of investment is hurting economic prospects, especially in a state like Illinois that is viewed as a transportation hub.

“People and business, they look to infrastructure in making their locational decisions. The extent that we’re not maintaining our infrastructure, we’re really undermining our economic base,” Luby says. “People aren’t going to locate there. Businesses aren’t going to locate there. So our tax base is going to decline.”

Msall says the state’s image is taking a blow, and that’s bad for business, too. “The real damage, in addition to the eventual tax increase and the unnecessary costs that are being incurred, is the reputational damage to the state of Illinois.”

Weinberg, with Truth in Accounting, says if there is any silver lining to the steady stream of bad budget news Illinois residents are getting, it’s that they might be better informed.

She says most Illinoisans were “lulled into a false sense of security” by politicians who’ve avoided the state’s ugly fiscal truths. So the average citizen “didn’t really pay attention to this as it was getting bad.”

Between the state’s lowest credit rating of any state in the nation, it’s massive unfunded pension liability and the drumbeat of headlines about the impasse over the last year, it’s harder to ignore. “I hate to say, it’s almost a good thing that they’re finally paying attention to this bad news and that they’re getting truthful numbers,” she says. “So that they can be knowledgeable participants in how we’re going to get out of this mess.”

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.