Illinois has a clear ambition for what it would like to do with members of its criminal class, and it’s right there in the name of the state agency set up to deal with them: the Department of Corrections. But there is a wide gap between ambition and practice. This is not to blame the department: politicians enacted the policies that have swelled the prison population, and politicians are largely responsible for the dire financial condition of the state that has squeezed agencies like the DOC. Nevertheless, the notion of correcting behavior has fallen victim to more basic needs, like keeping the doors locked and the lights on.

The department’s most recent quarterly report, on October 1, counts 48,903 inmates. Of those, just 8,254 are engaged in any sort of education or training program, including 2,773 in mandatory basic education, 1,933 earning a GED, and 2,076 in vocational training, such as auto body (47), barbering (36) and restaurant management (19). DOC spokesman Tom Shaer says 3,571 inmates are in drug treatment.

This is a long-winded way of saying there are tens of thousands of prisoners in Illinois, most of whom will soon be walking free, who are doing not much more than biding their time. They watch TV, they play cards, they listen to cassettes. As then-inmate Jeffrey McKenzie once told a visitor at the Vandalia Correctional Center: “They’re not correcting. This is just a holding facility, actually, because I don’t see any corrections whatsoever.”

A small group of state legislators have been meeting to consider whether Illinois ought to change the way it approaches crime and punishment. They’ve heard pleas to reduce mandatory-minimum prison sentences and to effectively decriminalize possession of small amounts of drugs. The John Howard Association, which monitors conditions in Illinois prisons, says unless something is done to control the ever-increasing population, Illinois could find itself in the position of California. Federal courts there have ordered the state to purge its dramatically overcrowded prisons. The people urging Illinois to lower its prison population include left-leaning civil rights activists and right-leaning budget hawks. But they share a common refrain: prison should be for the people we’re afraid of, not the people we’re mad at.

This raises a question: what do you do with the criminals we’re mad at?

Put that to policymakers and activists across the state, and one is likely to hear the same answer again and again: Adult Redeploy Illinois.

Created by the Crime Reduction Act of 2009, Adult Redeploy is a state program meant to keep men and women out of prison. It provides funding and expertise to local governments that want to divert offenders into specialized courts and an intensive form of probation. In exchange for the money, those localities agree to specific reductions in the number of people sent to state prisons. It represents what some officials hope will be the future of corrections — a change in philosophy that could improve the criminal justice system across Illinois.

Advocates say 'prison should be for the people we're afraid of, not the people we're mad at.' This raises a question: What do you do with the criminals we're mad at?

The purpose of Adult Redeploy is keeping men and women out of Illinois prisons. Through September 2014, Adult Redeploy says it has diverted 1,899 people from the Department of Corrections. At an estimated annual cost of $4,400 per person, compared to $21,500 per person in prison, officials say that’s saved Illinois taxpayers $41.6 million since the program was fully operational in 2011.

James Radcliffe, a retired St. Clair County judge and member of the Adult Redeploy Oversight Board, says the program keeps the community safer at a lower cost. And that’s not all: “A nice fringe benefit is you actually change behavior once in a while.”

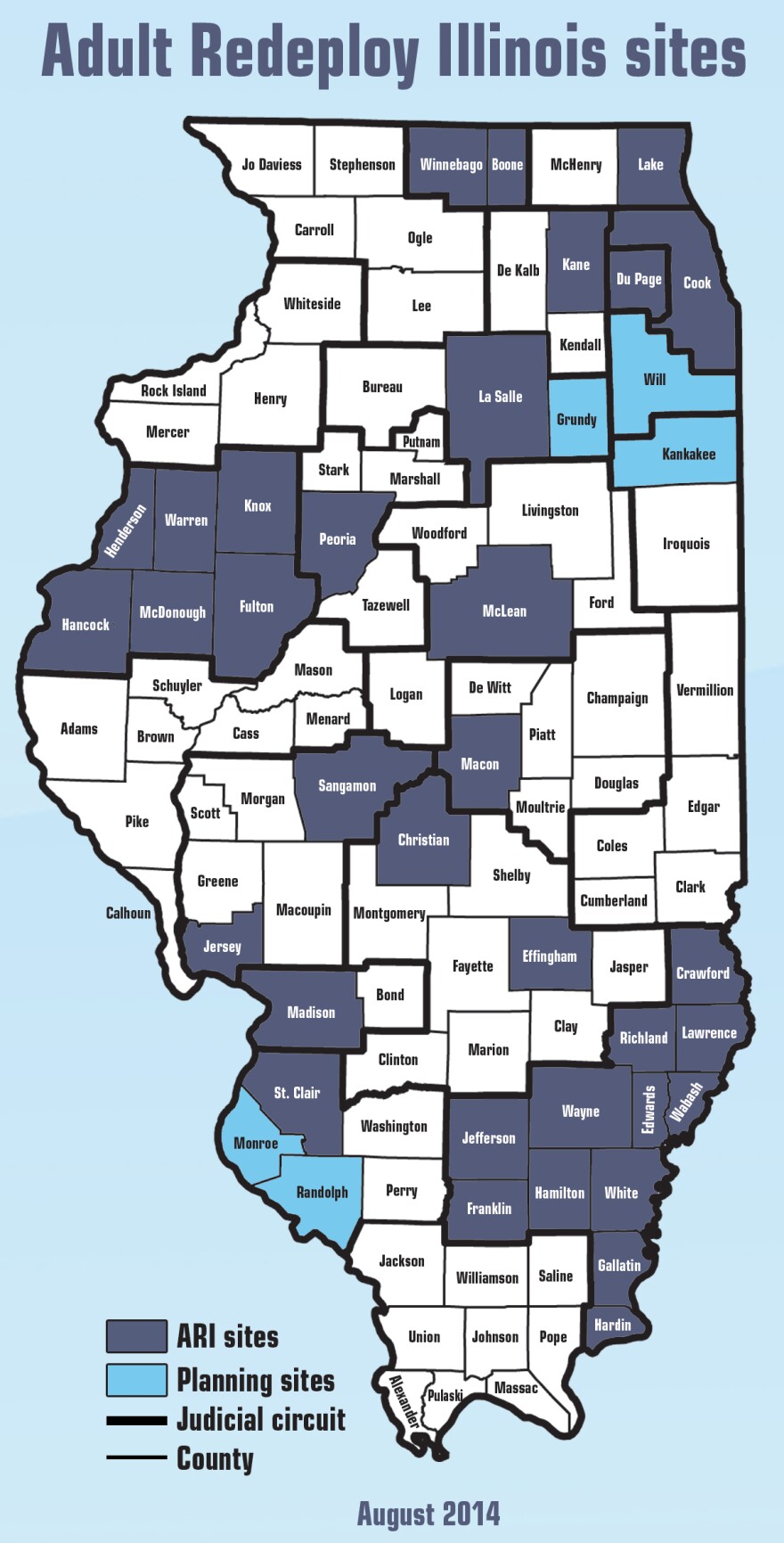

Radcliffe’s quip gets at a core principle of Adult Redeploy. Program director Mary Ann Dyar says one of the reasons Illinois’ prison system has become unmanageable is because a great number of non-violent offenders are, in her words, clogging up the system. Of the 23,909 men and women who entered Illinois prisons in fiscal year 2013, Dyar says 13,674 might have been eligible for Redeploy were it in place throughout Illinois, instead of just the 34 counties in which it operates. Such non-violent, low-level offenders are usually released before they can access meaningful rehabilitation, unlike, say, the 19 inmates learning restaurant management. They have what experts call unmet criminogenic needs — in other words, behavior and circumstances that contribute to crime.

Many are addicted to drugs. Others have untreated mental health disorders. Plenty have both problems. For years, some judges, lawyers and probation officers have recognized the special needs and opportunities of this population and created what are known collectively as problem-solving courts. Drug courts, mental health courts and veterans courts have been around for years — Cook County’s drug court dates to 1998 — but with Adult Redeploy, state lawmakers sought to formalize the system and provide incentives for more counties to adopt it.

To be eligible for an Adult Redeploy program, offenders are subjected to a risk and needs assessment. In Illinois, that’s done through an LSI-R, or Level of Service Inventory-Revised, a 54-point evaluation of needs that have been found to contribute to criminal behavior. Dyar says anti-social thinking and anti-social peers are at the top of the list. Farther down is substance abuse. Mental illness is not considered crime-producing, but it’s often seen in people who get in trouble with the law, and is often seen in conjunction with substance abuse.

“The risk assessment looks at those needs and scores the individual as to how prevalent these issues are in their criminal behavior,” Dyar says. “And then research will tell a practitioner what practices have been proven, in other jurisdictions with the same need, with a very similar target population, that will correct it and will reduce the chances that this person recidivates.”

It’s worth pausing to focus on two words Dyar used: “research” and “proven.” They’re crucial to understanding the way Adult Redeploy works. From the way courts and probation departments select and interact with individual offenders, to the criteria Adult Redeploy uses to fund local programs, the idea is to make evidence-based decisions — what research has proven will work.

On an individual level, the assessment is key, because research has shown not everyone will benefit from drug court or other intensive programs. Drug court in particular is for people who are likely to reoffend and have a lot of problems — so-called high-risk, high-needs individuals. Doug Marlowe, a lawyer, psychologist and researcher at the National Association of Drug Court Professionals, identifies three things to look for when deciding whether someone is or is not an addict, and thus whether they would be better served in treatment or with punishment.

First, addicts have what’s called a triggered binge response. Marlowe says this fits with the Alcoholics Anonymous dictum that one drink is too many, while a thousand are never enough. Second, addicts will have cravings or compulsions. Marlowe reduces this to a simple math equation: need > want. Third, addicts, when separated from their substance of choice, have withdrawal symptoms. Marlowe says addicts will do or give anything to make the compulsion go away — “take my body, take my baby, et cetera.”

Sending a casual drug user to drug court can actually make them into an addict.

Marlowe says sending a casual drug user to drug court can actually make them into an addict. He says the first drug courts treated low-risk, low-needs people. “That’s the only population the prosecutors would let us work with,” Marlowe says. Imagine a college student arrested for marijuana — perhaps the prosecutor thought she was doing him a favor by sending him to drug court, in order to prevent deeper involvement with the criminal justice system. “But it did the opposite,” Marlowe says. “We didn’t know.”

The type of targeting used by problem-solving courts on a micro scale, offender by offender, is replicated by Adult Redeploy on a macro scale, jurisdiction by jurisdiction. In order to get state funding, counties or judicial circuits must agree to divert 25 percent of a target population away from the Department of Corrections and into a community-based program. By law, only people convicted of non-violent offenses are eligible. Dyar says county-level data for that category of defendant is closely examined: “What types of offenses are they? Are they drug crimes? Are they property crimes? Are they high-level Class 1 felonies? Or are they low-level Class 4s?” Local government officials look for trends, try to determine what segment of the population they might serve and figure out which interventions would be appropriate.

Adult Redeploy is part of a three-prong effort to improve and expand problem-solving courts. One prong is the Administrative Office of the Illinois Courts — the bureaucracy through which the Illinois Supreme Court manages trial and appellate courts around the state. The AOIC is coming up with statewide standards for specialty courts. The second prong is a Rockford-based group called the Illinois Center of Excellence for Behavioral Health and Justice, which is helping jurisdictions comply with those standards. Adult Redeploy, prong three, provides the money to make it happen.

Michelle Rock, director of the Center of Excellence, says the Redeploy funding has been a key driver of expanding specialty courts in Illinois. Drug courts have been around since the 1990s, but before this new funding mechanism, she says they often depended on a judge championing the idea. Speaking of other people in the court system — such as prosecutors, defense attorneys and probation officers — Rock says, “When a judge calls a meeting, they show up.” She says specialty courts can be funded by county fees, “but some county boards are more supportive than others.”

Stephen Sawyer, a former chief judge of the Second Judicial Circuit Court, in southern Illinois, says he never felt confronted by skepticism when he was implementing drug courts in his jurisdiction. But he says it was probably there. “There are varying degrees of buy-in and commitment to this approach to law enforcement in this circuit, as there is in every circuit,” Sawyer says. Today, in “retirement,” he’s director of specialty courts for the Second Circuit. “Frankly, I think that particularly among state’s attorneys — of which I was one — and among law enforcement and some judges, this is not only a new way of operating within the court system, but it is also simply inconsistent with their views, or at least their habits, with respect to dealing with criminal defendants,” Sawyer says. “Among the elected officials of that set, I think that they really perceive that the public expects them to be more punitive.”

Of course, that’s not a universal view. Cook County’s director of specialty courts, Larry Fox, was a public defender and defense attorney in private practice for more than a decade before he became a Cook County judge in 1986. “It is very frustrating not to be able to do more with people than simply turn them over to the probation department,” Fox says, where conditions might be as minimal as reporting once a month, keeping up one’s address and so forth. Drug court, on the other hand, can subject participants to drug counseling, random testing and weekly meetings with a team led by a judge. It would be a mistake to think going to drug court instead of prison is the easy way out — “they’re not being offered a benefit,” Fox says.

Nevertheless, lingering skepticism is partly why Michael Tardy, director of the Administrative Office of the Illinois Courts, says drug and other problem-solving courts must have buy-in from stakeholders. “It’s kind of the show-me model: show me that it works,” Tardy says. From the perspective of the AOIC, he says accountability is key — the ability to measure the effectiveness and outcomes of these programs. For that reason, Redeploy Illinois collects and analyzes a prodigious amount of data.

Dyar, the head of Redeploy Illinois, says the local programs must be doing something different, and have to be sure they’re doing something that’s been shown to work. But even that can pose problems. “What a researcher says works doesn’t necessarily align with what an influential player is willing to do,” Dyar says. Heroin has been a particular problem for drug treatment professionals at every Redeploy site. “It’s just upended everything they’ve known works or doesn’t work,” she says, “and they’re just really struggling to stay ahead of the devastation it causes. Evidence has shown that medication-assisted treatment does work — drugs such as methadone and suboxone — “but there are a number of people in the treatment community who believe you have to demonstrate total abstinence,” Dyar says.

From that relatively narrow aspect of drug treatment to the wide spectrum of problem-solving courts in general, Dyar suggests these kind of evidence-based practices could change criminal justice. “Problem-solving courts are wonderful, but we need to generalize across the entire system,” she says. Thus, it should not just be the drug court judge who’s knowledgeable about addiction, but every judge. Dyar says that’s the way to really deal with the disproportionate minority contact and geographic disparity in the criminal justice system.

Like so many others seeking to overhaul crime and punishment, Dyar sees the present day as a turning point. “Even 15 years ago we didn’t have criminal justice research as a viable discipline. … And now we know what works. We know more than we even know what to do with,” Dyar says. “It’s just a matter of implementing that. And that is a matter of resources. But it’s also a matter of will.”

A version of this story was published in the January 2015 edition of Illinois Issues magazine.