Gray, bleak and desensitizing. Hope-draining and soul-crushing. That is how some who have entered the walls of the state’s super-maximum-security prison in Tamms describe it.

“The doors are like a rust-red color with thousands of perforated holes. And you look outside, and you don’t see nothing but a gray wall,” says Brian Nelson, a former Tamms inmate. “My biggest fear is that this is all happening in my head, and I am going to wake up and I’m in that cell. And that scares the s--- out of me.” Nelson has been paroled and now works as a paralegal in Chicago.

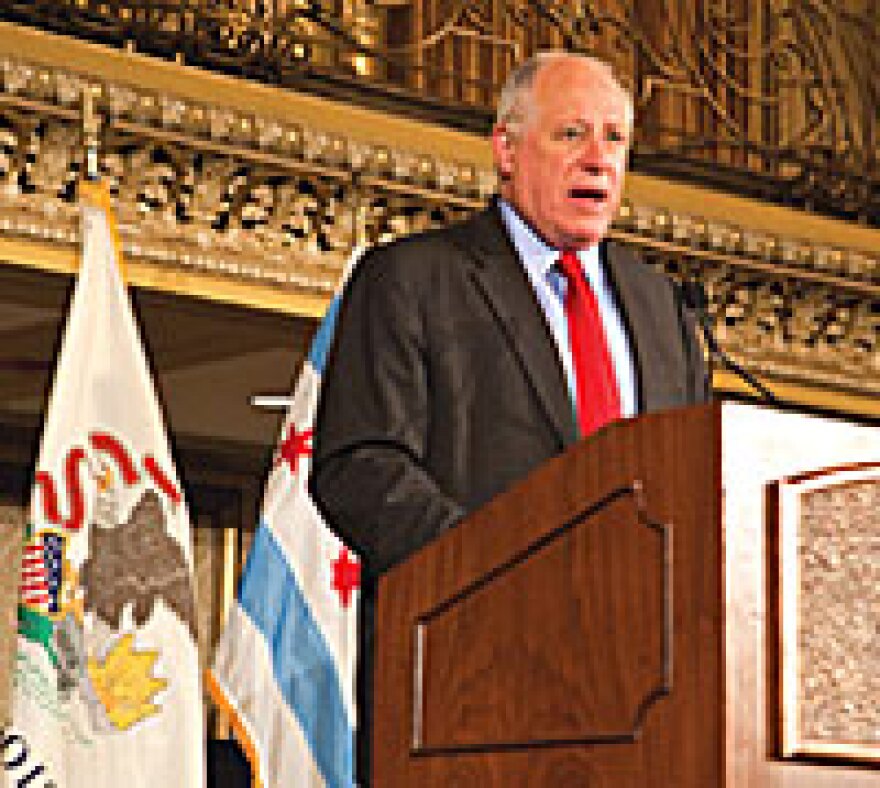

Many argue that without Tamms Correctional Center, the state’s prison system would return to a level of lawlessness it reached 20 years ago when gangs ran day-to-day life behind bars and assaults on guards and inmates were common. But Gov. Pat Quinn has proposed shutting down Tamms, based on the premise that the cash-strapped state simply cannot afford the costly facility, which holds fewer than 200 inmates who have been designated as high security risks.

***

There are differing opinions on what technically makes a prison a supermax facility, but the concept of supermax security is defined by extreme isolation. Prisoners spend up to 23 hours a day in their cells. They are fed in their cells and do not have the opportunity to interact with other inmates. Privileges, such as access to personal items, reading materials, television viewing, visits and phone calls, are strictly regulated. Such facilities are designed with sensory deprivation in mind, coupled with behavior modification techniques.

A federal prison in Marion in southern Illinois is widely recognized as having been one of the first modern federal supermax facilities in America and a model for all that followed. After the 1983 murders of two prison guards, the facility was put on lockdown, and inmates were confined to their cells for 23 hours a day. The practice ended when the facility was converted to a medium-security prison in 2007. But the federal government continued to use the methods pioneered at Marion in other facilities.

The conversion of Marion to a supermax prison ushered in a trend of states turning to such facilities to deal with disruptive or violent inmates, prisoners with gang ties and those dubbed the “worst of the worst.”

As the number of prisoners grew nationwide, so did the use of long-term isolation. A 2011 report from the New York Bar Association’s Committee on International Human Rights found that in 1980, there were 139 people locked up in state and federal prisons per 100,000 people. By 1990, the number more than doubled to 297 prisoners for every 100,000 people. In 2000, there were 478 inmates per 100,000 people. The number grew to 502 per 100,000 in 2009. By the end of 2009, state and federal prisons held more than 1.6 million people. “The relentless rise in the prison population over the past 30 years, during which the United States became the country with the highest rate of incarceration, created severe conditions of overcrowding and, increasingly, a public health problem. Faced with unprecedented numbers of inmates, prison administrators struggled to devise means to control the expanding numbers of inmates,” the report states. Supermax confinement became one method to address the problems resulting from the rapid increase in prison population.

By 2006, the country had 57 supermax facilities, with 40 states having at least one. At the time, wardens believed the prisons were working to make corrections systems safer. A 2006 survey by the Urban Institute found that 80 percent of wardens surveyed said supermax prisons had increased “staff safety and order” within their state’s prison system, and 75 percent thought that inmates were safer as a result of their state building a supermax.

But some wardens also had concerns about potential drawbacks. More than 30 percent said that the facilities limit inmates’ access to programs; 20 percent said they increase staff use-of-force incidents; and 12 percent said they increased the rate of mental illness.

Still, as awareness of the practices used at supermax facilities to handle problem prisoners grew, so did the belief that they were a step in the right direction for states facing overcrowding and violence in their corrections systems. A 2003 study from two corrections experts at the University of Minnesota said that “when state prison wardens visited and observed the unprecedented degree of control the Marion staff had over prisoners, several commented they ‘had died and gone to heaven.’”

An overcrowded and violent system was just what the members of the Illinois Task Force on Crime and Corrections faced when they sought to address the state’s prison problems with recommendations released in 1993. The group estimated that by 1996, the prison population would grow to a level that the state’s facilities could not accommodate. The task force determined that increases in drug-related and violent crimes met by stepped up enforcement was causing the number of inmates to grow. Such policies as mandatory minimum required sentences for some offenses, which had become popular during the push to be “tough on crime” and the War on Drugs in the 1970s, and that resulted in inmates spending more time behind bars. Drug offenses were categorized as more serious crimes and carried with them stiffer penalties. Illinois’ recidivism rate at the time — 46 percent — also was not helping matters.

Violence in prisons was on the rise. Assaults on prison staff held steady at about 1,000 a year in 1990, 1991 and 1992. The assaults were most prevalent at maximum-security facilities, but medium-security prisons saw an uptick in violence, too. “During fiscal year 1996, the majority of staff assaults by inmates — 986 of 1,219 — occurred at the four maximum-security prisons: Joliet, Menard, Pontiac and Stateville,” Springfield’s State-Journal Register reported in 1997.

According to the task force’s proposal, the growing population was also making it more difficult for prisoners to participate in programs geared toward rehabilitation, along with exacerbating the spread of infectious diseases. Even at that time, task force members feared sweeping court intervention. “This potential public safety crisis could undermine the entire criminal justice system and the public’s trust and faith in it. In short, something must be done immediately — and over the long run — to address the situation, or the state of Illinois may lose the opportunity to address the situation itself.”

The group recommended several steps that it emphasized must be used together as a cohesive plan to improve the state’s prisons. Among the task force’s recommendations: increases in staff and programs meant to rehabilitate prisoners, early-release programs for certain inmates who display good behavior, less harsh sentencing laws and the construction of a supermax security prison to manage “violent inmates.”

The logic of the committee was similar to that of a teacher sending a particularly unruly student to a timeout so the studies of the rest of the class are not disturbed. Violent and disruptive troublemakers in prisons caused situations, such as lockdowns, that made it difficult for their fellow inmates to participate in programs that could help keep them from coming back to prison. The task force warned that inmates should not be sent to a supermax for long periods to ensure that free space remain in the facility, so it could continue to serve as a deterrent. They also noted concerns about the psychological effects of long-term solitary confinement.

In the planning leading up to opening the state’s supermax, Gov. Jim Edgar voiced concerns about the cost of the $73 million prison. The operating costs were pegged at about $24 million at the time the facility opened. However, Edgar supported the facility as a way to try to bring order back to the state’s prisons. “It appears to be a very secure facility and not a place I’d want to spend much time in,” he told the State-Journal-Register when the prison in the southern Illinois village of Tamms opened in 1998.

Edgar says he has concerns about Quinn’s plans to close Tamms. “The thing that I would worry about, and the reason we built Tamms, was that often, you just had a few inmates that caused the problems in the prisons. I would be very nervous about taking the troublemakers and putting them back into the general prison population,” Edgar told WBEZ Chicago.

As states have been forced to make difficult budget choices, some have opted to scale back or close supermax prisons. Colorado, Maine, Ohio and Washington state have made changes to reduce the number of inmates kept in long-term solitary confinement.

Opponents to the conditions at supermax prisons say that those states are now pulling back from a policy that had murky goals and no clear track record and was an overreaction to prison problems in the ’80s and ’90s. “We just had a cycle of getting tougher and tougher,” says Laurie Jo Reynolds, founder of the group Tamms Year Ten that was pushing for reforms at the prison but now supports its closure. “It was very much a fear-based policy. There was no particular evidence that isolating people would be a way to deal with it.”

Mississippi recently closed its supermax facility, Unit 32, after several violent incidents, including a suicide. Budget concerns also played a hand in the closing. Christopher Epps, Mississippi’s commissioner of corrections, told the New York Times that he used to think that violent inmates needed to be locked up away from others and for as long as possible. “That was the culture, and I was part of it,” Epps said. Mississippi faced many of the same challenges, including overcrowding and violence, that Illinois and other states faced when Unit 32 opened in 1990.

But since his state has eliminated its supermax without violent incident, Epps has been converted to the idea that long-term isolation can cause more problems than it solves. “If you treat people like animals, that’s exactly the way they’ll behave,” he now says. That’s not to say that the state does not use isolation, or that all the prisoners from Unit 32 went directly into the general population. Many were still segregated at the prisons they moved to and had to earn privileges step by step.

***

Most of the prisoners currently serving time at Tamms have committed crimes that are fodder for sensational news stories and nightmares. One inmate shot and killed a young couple in a ditch by the highway and went on to stab an inmate once he was behind bars. Another is a serial predator who held a prison psychologist hostage and repeatedly raped her at the Dixon Correctional Center.

But reports have also filtered out about inmates being sent to Tamms for nonviolent infractions and of the facility being used as a place to warehouse prisoners, some for more than 13 years.

For a series called “Trapped in Tamms,” the Bellville News-Democratconducted an analysis in 2009 of the inmates at Tamms and found that the majority of them were murderers. However, of the 247 inmates, 138 had not been convicted of a new crime since entering the prison system. The paper said that 55 of the 109 who were convicted of a crime while in prison “committed assaults such as throwing body wastes or spitting on or struggling with guards, acts that did not lead to serious injury and can be attributed in some cases to mental illness.”

Critics of Tamms say there are no clear criteria for sending inmates there, and many prisoners end up in Tamms for behaviors that are symptoms of mental illness. Once they get to Tamms, the hours in isolation only serve to worsen their conditions.

Incidents of self-mutilation and suicide attempts are prevalent when prisoners are relegated to long-term isolation. One prisoner at Tamms cut off a testicle. While that act may seem almost impossible to imagine, two inmates did the same at Mississippi’s Unit 32 before it was closed.

Illinois Department of Corrections director Salvador Godinez testified during a recent Illinois House hearing that Tamms currently held probably no more than 25 prisoners who require the level of security and isolation that is found at the prison. However, the agency says that if the supermax prison is closed, it plans to continue housing Tamms prisoners in segregation at maximum-security prisons of Menard and Pontiac.

***

Quinn says that closing Tamms would save the state $26 million annually. According to IDOC, it costs an estimated $64,800 per inmate per year at Tamms, which is three times the cost of housing inmates at the state’s other prisons.

“I’m a taxpayer now. You can’t afford Tamms,” Nelson, the former inmate, recently told a Senate budgeting committee. “This is inhuman, but it’s also a waste of money.”

A convicted murderer who spent 12 years in Tamms, Nelson says that the isolation took a toll on his mental health. He said he never needed treatment or had suicidal thoughts before his time at Tamms, but he tried to kill himself in that facility multiple times. To hang onto his sanity, Nelson replayed happy memories in his head, such as a childhood trip to the Grand Canyon, and copied the Bible by hand, which he says took him “a year, nine months and two days.” Nelson said he knows that he had a debt to pay to society for his crime but that his time at Tamms will haunt him for the rest of his life. “I knew if I didn’t get paroled, I was going to die in Tamms. ... The day I walked out, my mom said, ‘What the hell happened to you?’”

But supporters of the facility say it is an invaluable key to keeping the rest of the state’s corrections system safe for prisoners and guards. They point to the fact that no prison guards have been killed since the facility opened. “Tamms has never been about saving money. No one ever said it would. Tamms has always been about keeping staff and inmates safe from the most dangerous and destructive inmates,” says Robert DuBois, a former corrections officer who worked at Tamms for more than a decade. “Tamms may be expensive to run, but can you really put a price tag on the lives you saved by Tamms being there, doing what it was designed to do?”

Stan Patton, a retired corrections officer who was stabbed while working at Pontiac Correctional Center in the 1990s, says that before Tamms, it was common for multiple stabbings to occur weekly at the state’s maximum-security prisons.

“I challenge the governor to sit down with 15 or 20 older correctional people that worked inside the [prisons], not just somebody that toured it but actually worked in there on a daily basis, to sit down with them and listen to what they had to say about how the prison systems were in the ’80s and ’90s and how it changed after Tamms was put online.” A legislative committee recently voted to advise against Quinn’s proposed closure of Tamms, as well as several other state facilities.

Those who say Tamms should be shut down point out that the last murder of a guard was years before Tamms opened and say other reforms put in place before Tamms have brought the system back under control. “There’s no evidence that Tamms turned things around,” Reynolds says.

Illinois Issues, June 2012