Last weekend, lawmakers elected Don Harmon to be president of the Illinois Senate. It’s been described as a bitter fight, but it has nothing on some of the conflicts from Illinois’ past, including one particularly “discreditable row” from the year 1857.

ESSAY — When Edwin Bridges walked onto the floor of the Illinois House, he was a man on a mission.

It was a familiar place, where he’d been appointed clerk two years earlier. But the clerk’s podium was no longer his place — a fact that would soon be made violently clear.

Bridges had been given the clerkship by the Whig Party, which by the time of the next election had seen many of its members convert to Republicans but lose its majority to Democrats. Now the other party would get to name the clerk, the speaker, and the doorkeeper, and enjoy the other spoils of majority rule. Bridges had to know this — but maybe there was a way to keep his colleagues in power.

?

Last weekend, members of the Illinois Senate’s Democratic caucus gathered in the spacious office designated for the use of the Senate president. After five hours of talking, wheeling, and dealing, they settled on Sen. Don Harmon, Democrat of Oak Park, for the top job. There was anger at the outcome, particularly from Sen. Kimberly Lightford of Maywood, who had sought the presidency for herself. But all things considered it was a relatively smooth transition.

Other changes in leadership have proven more difficult for Illinois lawmakers.

There was the time members of the Illinois House went through 93 ballots over three weeks before settling on Bill Redmond as speaker — he was the compromise candidate between the two Democratic power centers in 1975, Gov. Dan Walker and Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley.

Then there was time the Senate burned through 186 ballots before electing Thomas Hynes president in 1977. He later said the squabbling was a result of the power vacuum left by Daley’s death.

Four years later, Gov. James R. Thompson helped his Republican Party snatch the Senate presidency away from divided Democrats with a mere 29-vote plurality. That dispute had to be resolved by the Illinois Supreme Court, which held that winning the presidency required a 30-vote majority of the 59 seats in the Senate, not a majority of votes cast. The year was 1981, and incumbent Democrat Phil Rock was returned to the podium.

Those recent fights dragged on much longer, and with greater consequence, than the brief insurgency of Edwin Bridges, who tried to seize control of the Illinois House on January 5, 1857.

?

The 1850s were a time of turmoil in Illinois, as in many other parts of the soon-to-be-divided states of America. In March 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its infamous decision in the case of one-time Illinois resident Dred Scott, holding no descendent of slaves could be an American citizen, and invalidating the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which prohibited slavery in federal territories.

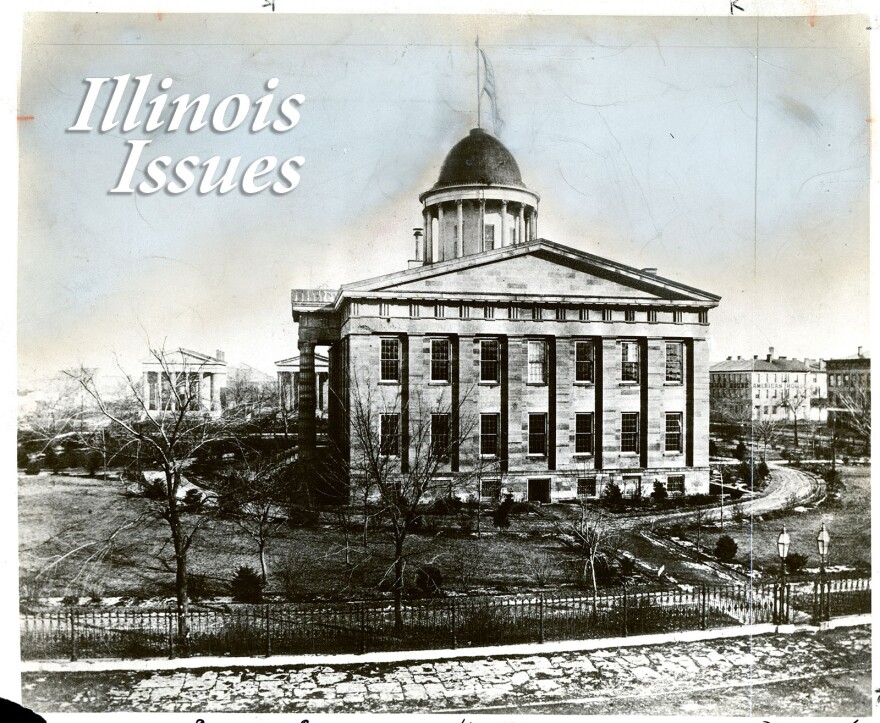

It is in this climate that the nascent Republican Party lost the legislative elections of 1856 to its Democratic Party rivals. (Around this time, many politicians who once identified as Whigs became Republicans, including a Springfield lawyer named Abraham Lincoln.) On the morning of January 5, as lawmakers convened in what is now called the Old State Capitol to open the 19th General Assembly, Bridges and his Republican allies set their plan in motion.

The House was called to order, a chairman was elected, and Capt. John McConnell was chosen to be the clerk pro tem — temporarily, just while the members got organized. That’s when Bridges approached the clerk’s desk and claimed that — as House clerk of the previous, 18th General Assembly — he was the presiding officer and had the right to call the roll of members-elect.

The Democrats ignored him.

Rep. John A. Logan, Democrat of Jackson County, who would become one of Sherman’s generals in the Civil War, moved to make Tevis Greathouse the doorkeeper pro tem. As Logan was nominating another man to be assistant clerk, Bridges cut in.

“I protest against these proceedings; I am the only sworn officer of this House, and have the right to require the credentials to be presented to me and the members sworn in,” Bridges said. “I shall insist upon it.”

Logan “called the gentleman to order,” but was diplomatic: “I wish to make one suggestion, and I do it with all due difference to the gentleman. I see no precedents for the old Clerk to organize this House; there is no law for it; there is no constitutional provision requiring it.”

Logan went on in this vein, but ended with a warning: “If the gentleman persists in disregarding the action of this House, I shall ask that the rule be enforced against him, and that he be expelled from the Hall of the House.”

As another member backed up Logan, Bridges was insistent on his position and his right to be heard. But other representatives were growing restless: “Put him out! Put him out!” they shouted.

One of Bridges’ Republican allies appealed to precedent: Rep. Issac Newton Arnold of Cook County, a personal and political friend of Abraham Lincoln, argued Bridges was correct, citing parliamentary law from Congress to England.

Things devolved from there: Clerk pro tem McConnell and Bridges began simultaneously calling the roll of members-elect.

Arnold, near the beginning of the alphabet, walked to the front the the chamber. He handed his credentials to Bridges — one imagines ostentatiously — “as being the person entitled to receive them.”

The Daily Illinois State Journal describes “great confusion — both Clerks proceeding with the call,” which was apparently a bridge too far.

“Order,” the speaker called.

“I call you to order, sir,” Bridges replied.

The Journal reports Rep. Eben Ingersoll from Gallatin County made the motion to expel Bridges. Another account attributes it to Logan.

“I protest, I protest,” Arnold said, amid cries of “Question! Question!” — the crowd’s way of saying it was time to vote on whether to expel Bridges.

The motion carried and — as the Journal rather bloodlessly reports — Bridges was removed, albeit "protesting against it.”

For a more vivid account of the day, one can turn to the St. Louis Republican, as reprinted a week later in — of all papers — the New-York Daily Times.

'After considerable wrestling, knocking over chairs, desks, inkstands, men, and things generally, Mr. Bridges was got out with his coat shockingly torn.'

The report says Greathouse — doorkeeper pro tem, though misidentified by the out-of-town paper as the sergeant-at-arms — “walked up to Mr. Bridges and politely informed him that he was directed to show him out. Bridges told him to keep his hands off, or he would get hurt. Greathouse took him by the collar, when Bridges struck him, and then commenced the scene.”

Members descended on the well of the House.

“After considerable wrestling, knocking over chairs, desks, inkstands, men, and things generally, Mr. Bridges was got out with his coat ’shockingly torn,’” the Times reports.

And that, it would seem, was that. The representatives were sworn in, and adjourned until the afternoon.

?

Most contemporary accounts did not withhold judgment: “An outrageous and at the same time an amusing scene occurred in the House of Representatives,” the Times wrote under the headline “The Illinois Legislature — Discreditable Row on the Organization.”

The Journal, a paper sympathetic to Republicans, called the incident “an unpleasant rencontre.”

The Democratic Daily Illinois State Register was harsher: “Previous to the organization of the house, we were witness of a scene, the like of which we hope never to see in an American legislative hall again.”

Though modern eyes read the Register as unabashedly racist — with its pro-slavery commentary and references to the anti-slavery Republican Party as “black republicans” — the paper provides the clearest explanation of Bridges’ scheme.

It seems the Democrats were two seats ahead of the Republicans in the House, and thus expected to take control. But two of their members’ elections were being contested, so “the opposition tricksters sought, by parliamentary trickery, to subvert the will of the majority.”

The plan was apparently for Bridges to leave those two contested Democrats off the roll call, and then with the support of a lone Whig, the Republicans would have enough votes to declare themselves in the majority.

“The tricksters failed all around,” the Register reports. “This high-handed attempt of a minority to usurp the power of a majority, will astound the people of Illinois, and will open their eyes to the precipice which they have neared in their recent elections.”

?

The main pugilists of Jan. 5, 1857 seem to have been otherwise honorable men.

The opposition Register asserts Bridges was “brought down from LaSalle [County]” and “induced” to participate in the Republican scheme, as “the supple instrument of their will.”

Born in New York, Bridges would soon find himself volunteering for service in the Union Army. In 1863 he would be included on a list of men Lincoln’s War Department appointed “commissaries of subsistence with the rank of captain” — an officer responsible for feeding soldiers. He served for more than three years with the infantry, fifth regiment, and was mustered out on July 31, 1866.

The afternoon of the incident, Greathouse would be elected the enrolling and engrossing clerk of the 19th General Assembly. He was later described as “one of those demonstrative men, with nobility of soul, and generous qualities of heart, which endeared him to all his friends. He was a man of fine education, a logical thinker and a profound legal intellect. He was ever ready to extend the helping hand to the poor and unfortunate.” He died in summer 1871, weeks before his wife, Julia, “leaving books, notes and accounts worth about $2000,” “many parcels of land some in Chicago,” and “one daughter, Adele.”

?

When the Illinois Senate met last Sunday, there was considerably less mayhem around Harmon’s elevation to the presidency. But he nevertheless takes over at a time of crisis for his party, and particularly for the Senate Democratic caucus. In the past year, three of his colleagues have been indicted, investigated or otherwise implicated in federal corruption probes. Before that, one of his colleagues lost re-election following an activist’s accusations of unwanted advances.

In brief remarks after taking the president’s oath, Harmon did not directly address these issues, but he did say this: “While we build on the success of the past, let also use this occasion to think about who we are, what the people need us to be, and how we can reset the tone of the culture here in Springfield.”

Resetting the tone of the culture in Springfield will be neither quick nor easy. The problems of Illinois government — whether corruption or parliamentary skulduggery — are not just a blemish on the body politic. They’re not even a cancer, deep in its bones. They're encoded in the state’s DNA.

Changing that will likely require nothing less than the slow work of evolution — aided in this case not by natural selection, but something rather more deliberate from the voters.

Brian Mackey covers Illinois state government and politics. You can email him, browse his story archive, follow him on Twitter — though he tweets but rarely — or subscribe to his RSS and podcast feeds.