A five-year effort to mark Missouri's most notorious slave prison will come to fruition next month, when a bronze historical plaque will be installed on the exterior of the Stadium East parking garage across from Ballpark Village and Busch Stadium.

This story was commissioned by the River City Journalism Fund.

Historians say the parking garage, owned by InterPark Holdings, is located on the site of a slave prison once owned by Bernard M. Lynch, a nationally known trader of enslaved men, women and children. Lynch operated several "slave pens" in pre-Civil War St. Louis, with the largest one beneath the site of the garage.

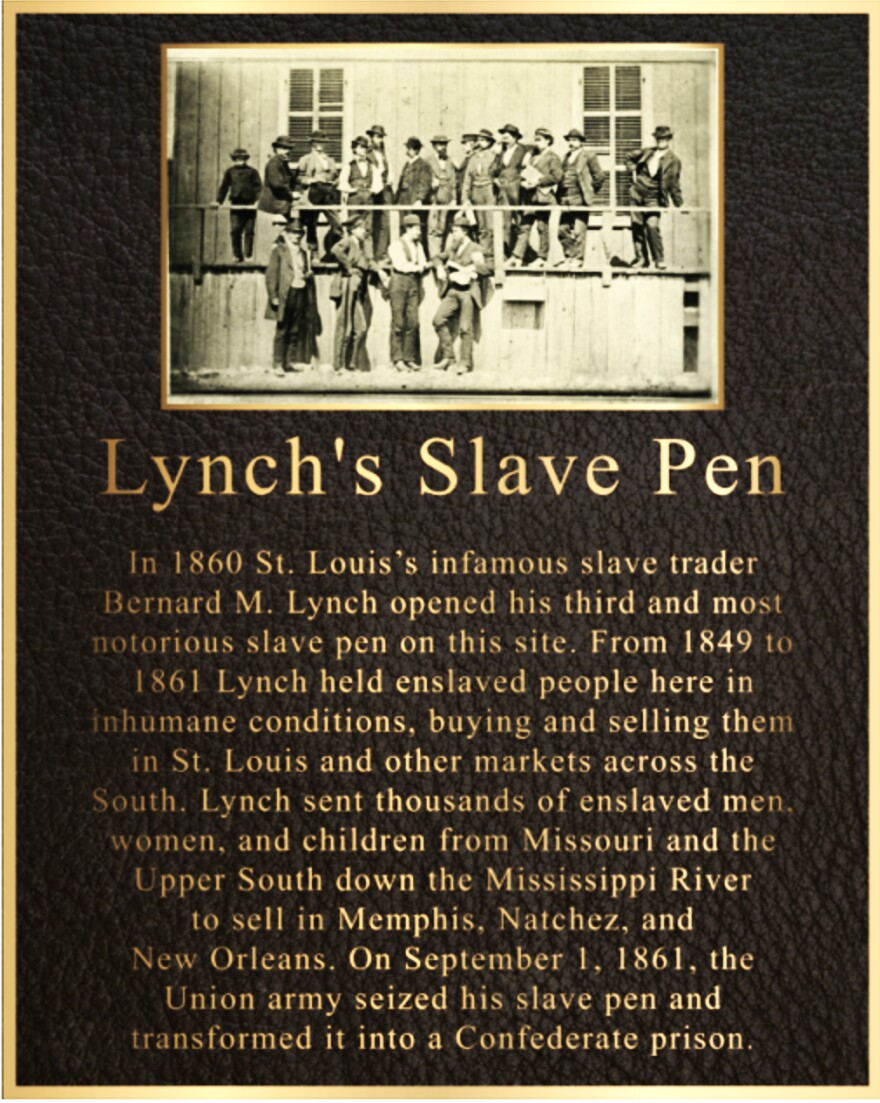

The project's backers are planning a ceremony in late January to unveil the new marker. On game days in the summer, they say, thousands of Cardinals fans will pass by the 20-by-16-inch bronze panel on the parking garage on Broadway; it will include text and a photo of one of Lynch's brutal slave prisons.

"From 1849 to 1861, Lynch held enslaved people here in inhumane conditions, buying and selling them in St. Louis and in other markets across the South," a mockup of the plaque reads in part. "On September 1, 1861, the Union army seized his slave pen and transformed it into a Confederate prison."

Among the project's supporters was the Missouri Historical Society, which agreed to contribute to the text and design of the marker and help preserve it after the installation.

"We are the preserver and the keeper of St. Louis' history, and that includes even some of the more dark sides of history," said Cecily Hunter, a historian with the society's African American History Initiative. "We're hoping that this will serve as a site for public education and remembrance."

Remnants of Lynch's prison cells survived in the basement of the Meyer Brothers Drug Company warehouse until 1963, when the building was destroyed to make way for the Cardinals' first Busch Stadium downtown. A Lynch slave pen marker that was installed on the warehouse by the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce was taken down and never replaced.

Historians say Lynch imprisoned thousands of people, many of whom were sold to buyers and shipped down the Mississippi River to work in the cotton and sugar cane fields of the deep South. After Lynch fled St. Louis at the outbreak of the Civil War, he worked in the mercantile business in Louisiana, according to former Missouri State Archivist Kenneth Winn, who helped write the text for the new marker.

Winn said Lynch later got married and joined the White League, a white supremacist paramilitary organization formed in the South after the Civil War. Lynch died a "happy man," Winn said.

The endeavor to create a Lynch slave pen marker was spearheaded by a group of politicians, historians and academics who came together after George Floyd's killing in 2020. Two state representatives at the time, Trish Gunby and Rasheen Aldridge, called for the Cardinals to help pay for a plaque that would acknowledge one of the prison's original sites, across the street from the stadium.

Gunby said she became aware of the issue after seeing a photo of Ballpark Village in a New York Times Magazine article by the 1619 Project. The article showed where Lynch's largest slave prison operated 165 years ago, near the corner of Broadway and Clark Avenue.

"When I saw that image, I remember a feeling of being shocked and sad that this history had been lost," Gunby said.

The marker, she said, "is how we move forward as a community in terms of addressing the racial injustice in our region."

Supporters say Gunby was the force who kept the project alive over the past five years. "I was just kind of the thorn that kept prodding everybody," she said.

Although Cardinals executives expressed initial support for the project and attended meetings with the group, they never agreed to fund it as a stand-alone project and ultimately decided against participating, according to Gunby and others involved in the discussions. Cardinals President Bill DeWitt III did not respond to messages seeking comment.

Gunby says she and her team continued to press for support from historical institutions. The logjam broke earlier this year, when the Missouri Historical Society agreed to get involved. Also, this fall, the Missouri Foundation for Health agreed to fund the cost for making the marker, estimated to be about $5,000.

The foundation's involvement "is deeply rooted in our being an anti-discrimination institution and recognizing the link that structural racism has to present day health disparities in Black people," it said in a statement. "The intergenerational trauma that the legacy of slavery caused is still relevant and continues to highlight persistent systemic issues and impact public health in Black communities."

InterPark, which owns the garage where the plaque will be installed, also helped make the project a reality, supporters say. InterPark could not be reached for comment.

Geoff Ward, professor of African and African American Studies at Washington University and director of the WashU & Slavery Project, worked with Gunby and others to create the Lynch slave pen marker. He says markers are an important way to bear witness to historic events.

"They convey information about the past — where we are and what's happened here — but promote values in the present and future," Ward said. "They convey respect for group experiences and the stories that deserve to be told, and in that sense they elevate certain values in the public sphere."

For more information about the River City Journalism Fund, which seeks to support journalism in St. Louis, go to rcjf.org.

Copyright 2025 St. Louis Public Radio