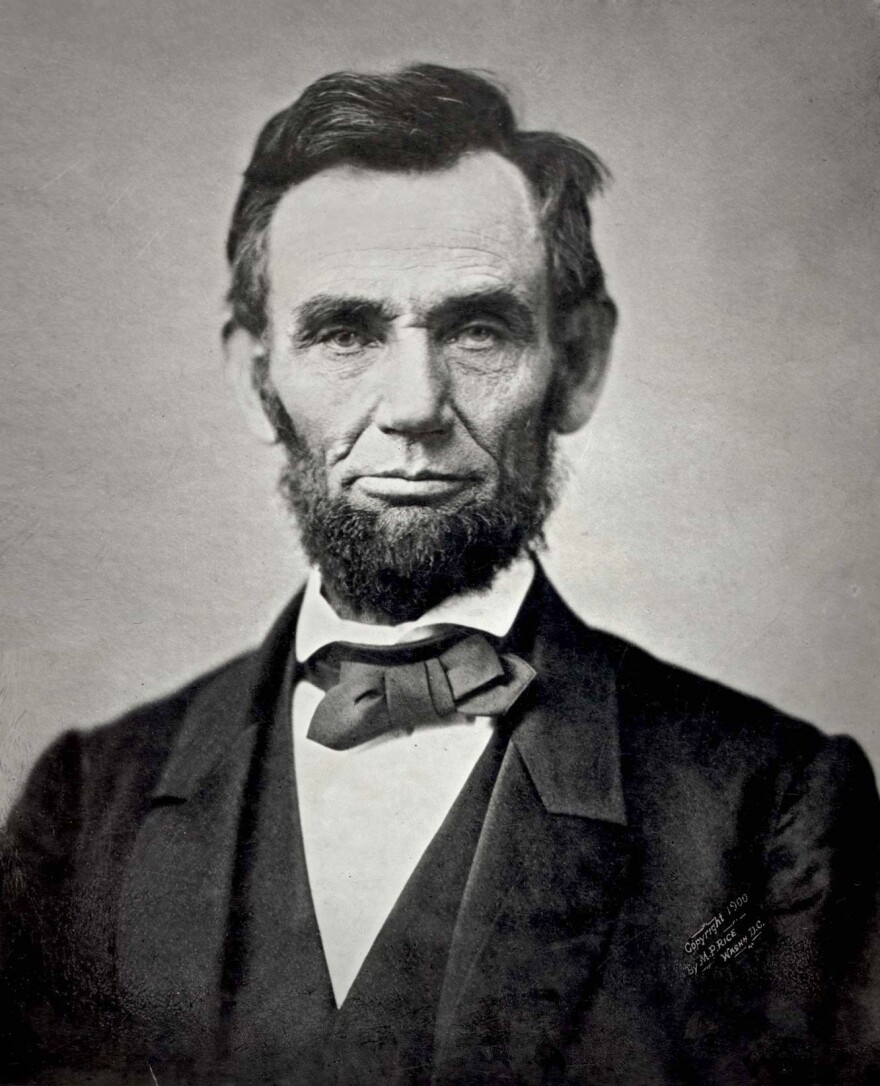

Was Abraham Lincoln, the “Great Emancipator,” a racist?

In recent years, some writers and scholars have argued that he was. They have reduced the complexities of his racial views to his brief support of the movement to colonize blacks in Africa. They have insisted that the Emancipation Proclamation was merely a military strategy, which did not become an instrument for social reform. They have argued that Lincoln was not quick enough to make the abolition of slavery a primary aim of the Civil War. They have suggested that abolitionists forced Lincoln to develop a higher moral agenda in conducting the war. They have argued that Lincoln was a white supremacist dedicated to the elevation of white society at the expense of the rights and freedoms of black Americans.

Some of these arguments are compelling, and some of them are outrageous. But to address the question of whether Lincoln was a racist, we need to understand the historical context of race. We need to make a distinction between evaluating historical actors on their own terms and evaluating them in terms of our own modern perceptions. We need to understand not only how Lincoln the politician understood race, but also how Lincoln the man responded to it in the context of the society in which he lived.

Understanding race within its historical context is the only way to get to the truth. Such current research projects as the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency’s Papers of Abraham Lincoln make available documentary evidence of Lincoln’s interactions with blacks, and an examination of that evidence enhances our understanding of Lincoln and his era.

First, some historical truths. In the first half of the 19th century, millions of blacks were enslaved. Free blacks in the North could not vote, serve on juries or hold public office. Southern states denied slaves the right to read, to write and to marry. Northern states, including Illinois, restricted the settlement of free blacks within their borders.

Most whites throughout the country held views of racial superiority over blacks. Public discourse of the period justified these racial constructs with biological, religious, legal, social and political rhetoric. Race determined the opportunities available to people in antebellum America, and only a small number of white individuals — such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Sumner, John Brown, and William Lloyd Garrison — envisioned, to varying degrees, a free society that included blacks as the legal, political and social equals of whites. At no time in American history had political and legal institutions recognized blacks as fully enfranchised citizens.

That racial reality is the context in which Abraham Lincoln lived, practiced law and politics, and served as president of the United States. Given this, it is necessary to recognize the enormous odds blacks faced in a society seemingly dedicated to the preservation of white superiority. It is equally important to understand how difficult it was for whites to endorse black freedom and equality. To be identified as an abolitionist or a proponent of black rights was not socially or politically expedient. In fact, it was often dangerous. The 1837 murder of Elijah Lovejoy in Alton, and the caning of Charles Sumner in the U.S. Senate in 1856 are only two sensational examples.

Lincoln the politician did not recognize blacks as his social or political equals and, during his years as a lawyer and office seeker living in Illinois, his opinion on this did not change. Lincoln was opposed to the institution of slavery during his entire lifetime but, like most white Americans, he was not an abolitionist. In ante-bellum America, abolitionists were a marginal, radical group, and most white Americans did not participate in or endorse abolitionist activities.

Perhaps Lincoln’s inability to embrace black equality in the pre-Civil War era and his failure to become involved in abolitionist activities demonstrates a weakness in his character. Perhaps it merely exposes the pervasiveness of inequality in the social, political, legal and economic institutions of antebellum America. After all, even most people who were courageous enough to call themselves abolitionists and participate in abolitionist activities, did not advocate social and political equality for blacks.

For some modern-day observers, this is simple math: Lincoln lived in a racist society; he did not view blacks as socially or politically equal to whites; and he was not an abolitionist. Therefore, Lincoln was a racist. But is there more to Lincoln than this equation?

During the 1840s, when Lincoln was establishing himself in Springfield’s legal, political and social circles, he was a frequent guest in the homes of individuals who held slaves. Yes, there were slaves in Springfield. Though Article VI of the Illinois Constitution banned slavery, there were slaves living throughout the state. It is likely communities simply turned a blind eye to these residents. But they would have been visible to Lincoln and, most likely, he had some degree of interaction with bondsmen. Unfortunately, there is no evidence to suggest how Lincoln might have felt about the slavery he witnessed in Springfield.

There were a number of free blacks living in Springfield as well. Abraham and Mary Lincoln employed two black women as domestic servants in their home. Many of Lincoln’s professional and personal acquaintances employed blacks. By 1860, 311 free blacks lived in Sangamon County. At that time, there was no structured residential segregation, and 21 blacks lived within a three-block radius of Lincoln’s home. One black woman was a member of Mary Lincoln’s church and another drove Lincoln to the railroad station when he left for Washington in 1861.

These black Springfield residents were Lincoln’s neighbors, and Lincoln was acquainted with many of them. There was a black shoemaker and at least two black barbers, one of whom was a Baptist elder. Local blacks owned property and some were activists, participating in the colonization society and attending an annual Springfield event that celebrated the 1834 emancipation of slaves in Haiti.

During his law practice, Lincoln had black clients and participated in cases that benefited black Illinois residents, and his third law partner, William Herndon, defended fugitive slaves. Lincoln defended a black woman in a criminal trial, helped three individuals escape convictions for harboring fugitive slaves and handled the divorce case of a local black couple.

In an 1855 slander suit, Lincoln represented William Dungey, a man with a dark complexion, who was struggling to prove his whiteness and maintain the privileges of white citizenship. Whether Dungey was “black” or “mulatto,” Lincoln understood the importance of his client’s fight to hold on to his white identity in a society that would take away his freedoms if his accuser was successful in proving his blackness.

Lincoln represented his clients, regardless of their racial identities, to the best of his legal abilities and took seriously his responsibility to them. One of Lincoln’s long-term clients was a Haitian-born black man, William Florville, a Springfield barber who owned a great deal of land. Beginning as early as 1847, Lincoln became Florville’s attorney. During the time of their lawyer-client relationship, Lincoln represented Florville in three lawsuits. He also handled legal matters related to Florville’s land holdings, including tax payments.

On September 27, 1852, Lincoln sent a letter to his friend and fellow attorney Charles Welles, asking Welles to help him out of a difficult situation. Lincoln was at court in Bloomington and was unable to follow up on a legal matter involving Florville. The letter is not extraordinary in the context of Lincoln’s legal practice. There are dozens of examples of Lincoln correspondence that detail his concern for his clients.

Lincoln wrote to Welles: I am in a little trouble here. I am trying to get a decree for our “Billy the Barber” for the conveyance of certain town lots sold to him by Allen[,] Gridly and Prickett. I made you a party, as administrator of Prickett, but the Clerk omitted to put your name in the writ, and so you are not served. Billy will blame me, if I do not get the thing fixed up this time ... .” The language is interesting. “Our ‘Billy the Barber’” could be taken as paternalistic and condescending, but Lincoln clearly does not wish for Florville to be angry with him. Florville was black and could not vote, so Lincoln wasn’t concerned about alienating a potential voter. Lincoln was “in a little trouble here” and did not want to risk his professional reputation or face the disapproval of a paying client.

The letter was respectful of Florville and indicated that he was a prominent member of the community. Welles also knew Florville because Lincoln referred to him in a familiar way. In this context, Lincoln and Florville had a typical lawyer-client relationship, and Florville’s race did not get in the way. Lincoln wanted Florville to respect him, but not because Lincoln was white and Florville was black.

Lincoln, like most lawyers, took cases that came to him without regard to his personal views regarding the clients or the cases and, like most lawyers, he approached the law from an amoral perspective. For example, Lincoln personally hated divorce, but he handled numerous divorce cases, helping clients to end their unsatisfactory marriages.

Evidence of Lincoln’s cases is contained in the Papers of Abraham Lincoln’s The Law Practice of Abraham Lincoln: Complete Documentary Edition, a three-volume DVD set with images of Lincoln legal documents. It provides examples not only of Lincoln’s willingness to advocate for black clients, but his willingness to take cases that harmed free blacks and slaves.

During Lincoln’s first law partnership with John Todd Stuart, Stuart wrote an indenture for a young black girl. And in a debt case, the partners represented a client who had failed to pay for a black female servant the client had purchased. In 1841, Lincoln handled a case in which one of Lincoln’s clients paid a debt by delivering a slave woman and her child to the creditor.

In 1847, Lincoln defended Robert Matson, a Kentucky slaveholder, who had brought five of his slaves with him to Illinois. While in Illinois, Jane Bryant, her son and her three daughters escaped from Matson and petitioned for their freedom. Matson retained Lincoln, who used the doctrine of comity, arguing that property owners could take their property (including their slaves) anywhere in the country as long as they were in transit and not in permanent residence in a free state. Fortunately for Jane Bryant and her children, the court disagreed with Lincoln, arguing instead that bringing slaves into the state was a “contravention of the Constitution of Illinois,” and declared the family free.

In 1857, after the U.S. Supreme Court delivered its opinion in the famous Dred Scott case, Lincoln publicly decried the outcome. In the 7-2 decision, the court upheld the federal case in Missouri in which a black man had petitioned for his freedom. Interestingly, Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney supported the opinion of the court by citing the doctrine of comity, making the same argument that Lincoln had made when he defended the slaveholder Matson 10 years earlier. The court’s decision not only denied Dred Scott his freedom, but it declared that blacks were not eligible for citizenship.

The decision sent a shockwave across the country, as proponents of slavery celebrated the high court’s protection of the institution and as opponents of slavery, like Lincoln, denounced it.

Lincoln’s opposition to the Supreme Court’s decision provided a target for Stephen A. Douglas in the Illinois senatorial debates the next year. Douglas argued that by rejecting the Dred Scott opinion, Lincoln had declared “warfare” on the Supreme Court and was advocating black citizenship and equality.

In the first of the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates in Ottawa in August 1858, Lincoln countered Douglas’ accusation by stating: “I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is physical difference between the two, which in my judgment will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality.”

Throughout the debates, Douglas repeatedly accused Lincoln of advocating racial equality, and Lincoln repeatedly refuted this charge, sometimes with stronger language than he had used in Ottawa.

In the 1858 campaign for the U.S. Senate, Douglas was a vocal proponent of white supremacy, and he was Illinois’ proslavery candidate. Abraham Lincoln did not advocate black and white equality, but he was Illinois’ antislavery candidate. Douglas won the election, but two years later the political climate had changed. In 1860, when Lincoln was the Republican Party’s candidate for president, he was, essentially, the same candidate he had been during his campaign for the Senate. He was still opposed to slavery, and he still did not embrace racial equality. This time, however, the party with the antislavery platform won the election.

Throughout his lifetime, Lincoln had contemporaries who were more radical on the question of race than he was, and he had contemporaries who were more conservative. Lincoln enjoyed meaningful personal and professional connections with individual black people, yet it took four years of bloody Civil War to begin to change his attitudes about the possibilities for black freedom and equality. Did these attitudes make Lincoln a racist? Or do they reveal complexities in his character?

If we employ our modern definitions of race and racism, we cannot see the complexities of Lincoln’s character and we cannot examine the contradictions within the man. If we dismiss Lincoln as a racist, then that is the end of the story because he was no different from the proslavery Douglas, for example, and there is no point in investigating the matter any further.

It is important to remember that human beings — in the present as well as in the past — are flawed, complicated and contradictory.

Lincoln was not immune from the complexities of human nature. In the end, the limitations of Lincoln’s own racial perspectives were an indictment of the larger society.

Much of American history was not pretty, but the complexities and the contradictions of the various historical experiences of the human condition provide a much more truthful picture of our racist past than does boiling down the details into one word with which we are only beginning to come to grips.

From the Papers of Abraham Lincoln

The Web site of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln now features searchable online access to a day-to-day chronology of Lincoln’s life.

The project produced an expanded online version of the book Lincoln Day by Day, a compilation of work by Lincoln scholars that was published by the Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission in 1960. The project’s electronic version, titled The Lincoln Log: A Daily Chronology of the Life of Abraham Lincoln, is available by clicking an icon on the Web site: www.papersofabrahamlincoln.org.

Staff of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln, a project of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency that is co-sponsored by the University of Illinois at Springfield, is compiling all known documents written by or to Lincoln in his lifetime for comprehensive production in electronic form, as well as publication of volumes of selective materials.

In 2000, the project released on DVD its compilation of the known documents from Lincoln’s law practice. Also available online is access to a curriculum on the project geared toward high school teachers.

Stacy Pratt McDermott, an assistant editor for the Papers of Abraham Lincoln, was a contributor to In Tender Consideration: Women, Families, and the Law in Lincoln’s Illinois, which was published by the University of Illinois Press in 2002.

Illinois Issues, February 2004