It was a logical step for a state that granted suffrage rights years before.

“Put Illinois over first!” was the battle cry of suffragists 100 years ago this month, reported Springfield’s June 9, 1919 Daily Illinois State Register. They were at the Statehouse lobbying for the Prairie State to be the first to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would give American women the right to vote. Congress had passed it on June 4 and 36 states had to approve it to become law.

It took Illinois less than sixty minutes.

Within one hour of convening the next day, the Illinois House and Senate approved the measure, making Illinois a leader in women’s enfranchisement. The vote was unanimous in the Senate while three lawmakers dissented in the House. One called the Amendment “distasteful,” according to the House Debates record.

Wisconsin and Michigan ratified the measure later that day. Because of a typo in papers from Washington, Illinois had to redo its vote the next week, says Dave Joens, Director of the Illinois State Archives. Now, Wisconsin claims it was first, but Illinois held its initial vote before our northern neighbor and no technicality can change that.

Illinois being the first was a bit anti-climactic. Our ratification vote was expected. The big fight was six years earlier when the Illinois General Assembly voted on partial suffrage for women in the state, according to Mark Sorensen, retired assistant director of the Illinois State Archives and author of pieces on Illinois’ suffrage history. It required Herculean efforts of Illinois suffragists, who used creativity and sometimes might (one blocked opponents’ lobbyists from the House during the vote, according to “The Concise History of Woman Suffrage” by Buhle and Buhle). An extreme tactic, but some were battle-weary,, having fought for 40 years.

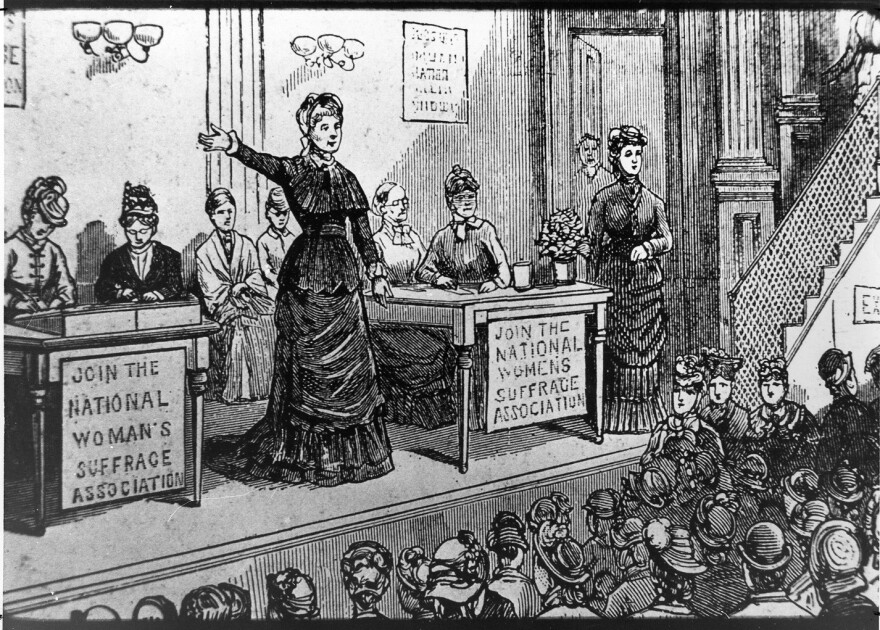

The earliest suffrage organization in the state formed in 1855 in Earlville, west of Chicago, according to the Illinois League of Women Voters. The Prairie State was “a hotbed of suffrage,” says Lori Osborne, director of the Evanston Women’s History Project and the house museum of Evanston suffragist Frances Willard, president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). It was “the largest woman suffrage organization in the United States by the 1880s,” according to Osborne.

Suffrage opponents blossomed here, too. In 1896, Chicagoan Caroline Fairfield Corbin established the Illinois Association Opposed to the Extension of Suffrage to Women. She argued that women’s place was in the home, not working outside of it or voting, which would lead to “bickering and rivalry” between the sexes, according to the Association’s 1909 booklet, “Why the Home Makers Do Not Want to Vote.” She quoted “Dr. Evans, Health Commissioner of Chicago: ‘Nearly all of our economic problems would find solution, and many of our hospitals and graveyards would be deprived of a large percentage of their occupants, if women, from highest to lowest, were educated to do, and did do, their duties in their houses.’”

Women voting was a fairly radical idea, which the WCTU fought by reversing opponents’ argument. It posited that women needed suffrage for “home protection,” says Osborne. Suffragists’ counter argument was: “If there’s a woman’s sphere and it’s the home and childcare, then women should be allowed to vote for things related to children and to control liquor sales because liquor wrecks families,” says Sorensen.

That strategy won -- initially. In 1891, Illinois passed a law allowing women to vote for school officials. “It established a precedent,” says Steve Buechler, a retired sociology professor and author of “The Transformation of the Woman Suffrage Movement: The Case of Illinois, 1850-1920.” “For the next 20 year or so, they tried to get bills passed for township suffrage, village suffrage -- all kinds of variations on that model.”

But the strategy had a downside. Nationally, suffrage was a hard sell. The liquor industry didn’t like the home protection argument because they worried that women would vote for prohibition.

Women’s enfranchisement faced other issues, too. It was largely a movement of white, middle-class women. “Part of the argument for woman suffrage was, give white women the vote and that will cancel the black (male) vote,” says Osborne. “White women are often excluding African-American women from the movement.” The reasons were “prejudice” and “strategic calculation,” says Buechler. “I think middle class women in the suffrage movement would have been happy to welcome the enfranchisement of black women, but they feared if they made it too big a part of their program, policy or events, it would spark a backlash.”

In Illinois, suffragists’ biggest success came in the early 1900s. Buechler thinks that’s because the movement finally united women of all classes when they sought the right to vote for Chicago city officials. Although they failed, the effort brought together conservative women’s clubs who were becoming more community-minded, working class and immigrant women who were concerned about the workplace and economy, and wealthy women who couldn’t vote on the taxes their property was assessed.

In 1913 this now united movement lobbied for statewide presidential suffrage -- the right to vote for certain local officials as well as presidential electors. Grace Wilbur Trout, an Oak Park author, mother, and head of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA), instituted a highly organized campaign focused on education and the personal touch. The IESA kept detailed cards on each lawmaker to determine the best person and strategy to sway him.

Their success was far from certain. To bolster support, the women arranged constant phone calls to the House Speaker and transportation to the Statehouse for allied lawmakers to make sure they didn’t miss the vote.

It worked. Illinois became the first state east of the Mississippi River to give women the right to vote for president, according to the Illinois State Archives.

Six years later, when states had to take a stand on the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, Illinois’ ratification was virtually assured. But full ratification wasn’t. Southern states weren’t crazy about suffrage, yet it squeaked by. In the summer of 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to approve it and the Nineteenth Amendment took effect on August 26, 1920, just in time for women to vote in that fall’s presidential election.