Amid the debate about the nation’s widening gap between rich and poor — a reality amplified in the State of the Union address — the numbers in Illinois paint a particularly striking picture.

It’s not your imagination. Multiple studies and census figures point to the rich getting richer and the poor and middle class treading water or losing ground all across the nation, but Illinois is among the states with the most pronounced divide.

In Illinois, the top 20 percent of households make about eight times what the lowest fifth make, according to a report by the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the liberal-leaning Economic Policy Institute, which are based in Washington, D.C. The report ranked Illinois ninth highest among states in terms of income inequality.

Other Illinois statistics help tell the story:

— The richest 5 percent of households in Illinois have average incomes nearly 15 times as large as the bottom 20 percent of households and nearly five times that of the middle 20 percent.

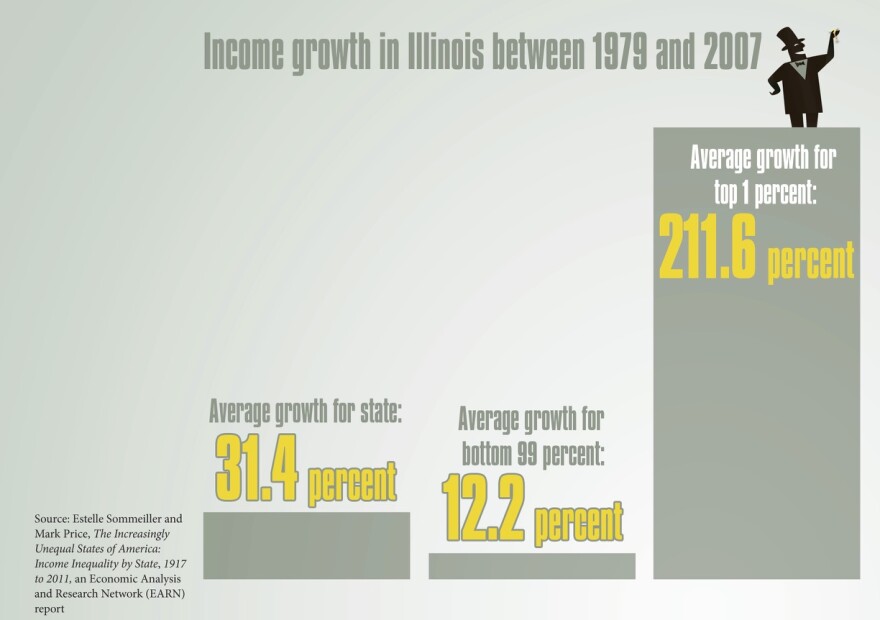

— From 1979 to 2007, though the average inflation-adjusted income growth overall for the state was 31 percent, the gains went primarily to the top. The income of those in the top 1 percent in Illinois grew 212 percent while that of the other 99 percent grew an average of only 12 percent, according to a February 2014 report by the Economic Policy Institute.

— The average income of Illinoisans in the top 1 percent is 24.5 times greater than the average income of the remaining 99 percent. The average income for the top 1 percenters in 2011 was $1,083,216 and $44,210 on average for the remaining 99 percent.

That gaping divide has not always been the case, says Jennifer Clary, author of the report 50 Years Later: a Report on Illinois Poverty, and an associate at Social IMPACT Research Center at Heartland Alliance.

“We have heard the notion that a rising tide lifts all boats. For a number of decades after WWII that was rather true,” she says. “We saw productivity go up along with wages for the executive as well as the lowest paid workers. In the 1970s, that began to change. Productivity continued to rise, but that stopped translating into higher wages for most workers. In fact, those gains really stayed at the top. The value of the minimum wage has eroded over time.”

Jobs have changed as well, she says. The jobs accessible to people with low education are far less likely to pay family-supporting wages and health benefits than they once were, she says.

The report also finds that the ranks of the working poor have swelled.

Now 388,000 in Illinois live in a household where someone works full time year-round but can’t rise above poverty level because the wages are so low.

Gloria Currier of Chicago knows the struggle of working full time but just getting by. She’s at the top of her wage bracket in her job as a cashier in a drug store, where she has worked for 15 years, and her pay is frozen. But her expenses aren’t frozen, which makes it harder and harder to pay the bills.

She raised two children alone after a divorce 40 years ago and wanted to retire at age 62. But now at 63, after losing a good chunk of her nest egg in the recession and still saddled with mortgage payments, she doesn’t see how she can stop working full time any time soon.

“How can Congress say the economy’s coming back? I don’t see it, and many people do not see it,” Currier says. “What about the poor Joes who can’t make ends meet?”

And although there are more women, like Currier, in the workforce than there were decades ago, that hasn’t helped narrow the income gap among households.

Women tend to be overrepresented in the lower-wage, less-skilled, more volatile jobs, so they tend to be in jobs that don’t have paid sick leave. That has a disproportionate impact on women when you consider that women are far more likely to have caregiving responsibilities whether for children or other family members, Clary says. The report found that the average cost of child care in Illinois is $1,496, more than the monthly earnings of a worker making minimum wage ($1,430).

There’s also the persistent wage gender gap, she says. More women are leading households, but on average they don’t make as much as men. “So even though women’s labor force participation has nearly doubled and gone from 36 percent to 61 percent (since 1960), they are still earning 77 cents on the dollar compared to men.”

Reasons abound for why the wage gap trajectory persists. Some say the global economy is to blame — that corporations in the U.S. have to compete with economies in other parts of the world that pay workers much less.

Some say the gap is widening because middle-class manufacturing jobs are being outsourced to other countries and are being replaced here with lower-paying service-industry jobs.

A working paper by a team of economists, led by Jeremy Greenwood of the University of Pennsylvania, suggests that the reason may lie in the increase in people marrying partners with similar education levels. The better educated marry those also better educated and both get jobs that increase household income. Those with less education are marrying those of similar education and making less and the split grows, they reason.

Frank Manzo, policy director of the Illinois Economic Policy Institute, says among the measurable reasons for the gap, the most significant is the decline of union membership.

In Illinois, union membership was only 15.8 percent last year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, down from 27.3 three decades earlier. In a January 2014 report he cowrote, Manzo notes that being part of a union has meant a premium on wages of between 10 and 17 percent.

Union membership relates more to the low-income and middle-income workers so when union membership declines, that tends to drag down the wages of a larger percentage of those on the lower end of the income scale.

The report states that income inequality in America has risen to levels not seen at any time since the late 1920s.

The recession of 2009 narrowed the gap a bit, Manzo says. Everyone was hit hard, for different reasons. Investments and stock prices plummeted, but the hardest hit were those who lost their jobs. Those at the very top lost more in terms of stocks and investments.

But since the recession, the paths for the rich and poor have been very different. Stocks and investments are climbing again. Manzo’s report notes that, “the average CEO earned 29 times the amount of his or her workers in 1978, 122.6 times the compensation level in 1995, and 272.9 times greater in 2012.”

But at the lower end of the income spectrum in Illinois, unemployment numbers haven’t recovered from the recession. Illinois is saddled with the third- highest unemployment rate in the nation (behind Nevada and Rhode Island). As of April, it was 7.9 percent, much higher than the national average of 6.3 percent.

All of these forces are working toward increasing income polarization. The meaning of that depends on your point of view.

If your perception is that people get paid more because they invest in their training and education and work harder, then you may see the income gap as a natural progression and a good thing, Manzo says. Higher wages act as an incentive and encourage entrepreneurship.

“But if we’re worried that people who are working hard but don’t get what they deserve — then income inequality is bad,” he notes.

What most agree on is that opportunity should be there for everyone.

Among the costs of income inequality is that opportunity becomes polarized. Education is one of the best examples.

Costs of college have soared 27 percent beyond the rate of inflation from the 2008-2009 academic year to 2013-2014 academic year, making it increasingly difficult to obtain for those with lower incomes. Without higher education, the higher-paying jobs are more out of reach, which feeds the divide.

“We would like for the poor child to have the same educational opportunities as the rich child. They may both have the same potential, but the rich child may be able to achieve their full potential more easily than the poor child because they have these opportunities — education, connections, access to credit. That becomes polarized when there’s income inequality. Also when the talents of potential workers go unrealized — that causes inefficiency,” Manzo says.

There’s also a question of fairness, says Elizabeth McNichol, senior fellow with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ State Fiscal Project. “Economic growth comes from the contributions of everyone all across the income scale, and it’s counter to the American way in fairness if people aren’t all benefiting from that growth.

“And at some point people get discouraged. They see their kids aren’t doing as well as they did, and even if you work hard, you don’t get ahead. It doesn’t encourage you to work even harder.”

Governments can certainly push back against these trends, McNichol says. “It’s definitely not inevitable that it has to be like this.”

In Illinois, state taxes and budget policies are exacerbating the problem, she says.

A 2013 report from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, ranked Illinois fourth highest for most regressive tax system.

The state’s financial imbalance has inspired a push by unions, education groups, community organizers and government reform advocates for a constitutional change that would allow lawmakers to approve a graduated tax, where people who make more pay a higher tax rate, instead of the current flat tax, which means all pay the same rate.

To get the change on the 2014 general ballot, three-fifths of the members in both chambers of the General Assembly would have had to have voted in favor of an amendment by May 4. It didn’t happen this legislative session.

Gov. Pat Quinn says raising the minimum wage from the current $8.25 to at least $10 would also attack income inequality and would help the more than 400,000 minimum wage workers in Illinois. Business leaders argue that would drive business to neighboring states where minimum wage is already lower by a dollar. Voters may get to weigh in on the issue through a nonbinding ballot question in November.

Illinois is not alone in wrestling with the minimum wage issue. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, as of April, 38 states considered minimum wage bills during the 2014 session and 34 are considering increases to the state minimum wage.

“The fact that taxes have not kept up with needs in the state means it can’t invest as much in education or things that could help them move up the income ladder,” McNichol says. “When you have a fairly regressive tax structure as Illinois does, even when the economy grows and personal income grows … you’re always perpetually falling somewhat short.”

Marcia Frellick is a Chicago-based free-lance writer.

Illinois Issues, June 2014